|

Home Updates Hydros Cars Engines Contacts Links Contact On The Wire |

Tethered Car and Hydro Engines

It is not the intention of this page to provide an in depth history of the development of engines used in tethered cars and boats as that subject has been covered extensively in numerous books and periodicals over the years. It should however serve to give a flavour of the way that motors, both commercial and home built, have shaped these two intensely competitive disciplines.

Whether it is a tethered car or hydroplane, the one essential ingredient for a successful run is an appropriately powerful engine. The design of hull or chassis must not be underestimated and the ability of the builder to establish a set up which has all the elements working together perfectly is vitally important. However, it will ultimately be the performance of the engine which determines the success or otherwise of the boat or car. Tethered hydroplane and tethered car racing began in very different eras, which in many ways dictated the way the sports progressed. Internal combustion engines were still in their infancy when first put into model or full sized boat hulls. By the time tethered cars became popular, the miniature IC engine was firmly established with a thriving commercial market directed primarily to aeromodelling.

It is well accepted that going quickly on water is much more difficult than on land. It took from 1908 to 1972 to exceed 100mph with a tethered hydroplane in the UK, yet in less than 10 years from the first car appearing in Britain, Gerry Buck had exceeded 100mph, and with an engine that he had built himself. In the early 1900s model speedboat builders were dealing with a power source that had only been in existence for such a very short time and the very act in 1908 by Herbert Teague of tethering a hydroplane was enough to start some serious harrumphing, end of the sport, not the behaviour of a gentleman, unfair etc. and as for the use of ‘noisy, smelly petrol engine’, scandalous.

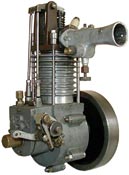

Indeed, steam engines were the power source used in the first racing model boats, soon superseded in the first decade of the 1900s by the flash steam plants with the boats of Teague, Delves-Broughton, Fred Westmoreland, Bert Groves, Ted Vanner and later Stan Clifford maintaining a stranglehold on the outright record for many years.

This was primarily because the internal combustion engines that were available at the time were crude, very large and heavy, slow revving and required ancillaries that were also in their first throes of development. Many persevered with IC motors, yet flash steam would remain dominant into the 1930s. This did not stop commercial involvement from the very earliest days with Stuart Turner and W.J. 'Belvedere' Smith both producing four-stroke motors that were in use well before the First War. Very quickly, several manufacturers, which included Bond's 'O' Euston Road, Economic Electric, Gray's of Clerkenwell, Gamages and even Bassett Lowke were producing motors suitable for hydroplanes. Several of these motors were early examples of 'badge engineering' being variations of the same design by F.N. Sharpe of the South London Experimental and Model Powerboat Club.

|

|

|

|

| Smith 'Belvedere' 1910/11 | Stuart Turner AE 1913 | F.N. Sharpe original1928 |

Bond's Simplex 1931 |

It was however the designs and home built motors of the Innocent Brothers, Ken Williams, Stan Clifford and George Noble that would break the flash steam domination. All these motors were 30cc single cylinder, yet as the four-stroke IC motor eclipsed the flash steamers in the 30s, so they in turn were consigned to a supporting role by the highly developed two-stroke motor. By 1948 the outright hydroplane speed record had risen to 51.17 mph, held by ‘Faro’, a 30cc ‘A’ class boat and engine that had been built in 1935. A year later a 10cc ‘C’ class boat held the record at 70.1mph, nearly 20mph faster, entirely down to the use of a commercial two-stroke motor.

|

|

|

| Mid 1930s four-strokes from the Innocent Brothers, Ken Williams and George Noble | ||

The use of two-stroke motors was far from new as they had been utilised in boats almost from the word go, and as far back as 1925, Gems Suzor surprised all concerned with a 16mph run at the Grand Regatta. This was not fast in the scheme of things, but with an engine of just 17cc was enough to make people take notice. Suzor continued to develop the two-stroke theme, along with Andrew Rankine and his highly successful ‘Oigh Alba’ and a raft of others, such as messrs Row, Mitchell, Bowden, Buck and Duffield to name but a few, but it was George Lines and his ‘Sparky’ engine that really boosted the popularity of the two-stroke for boats in Britain, as here was a motor, simple to build, very fast, as his string of successes would attest to, and easily scaled up or down for A, B or C class racing.

|

|

|

| Gems Suzor | Meageen/Rankine | George Lines' 'Sparky' motor |

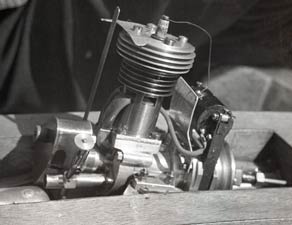

The racing of model cars began some while after that of boats, and whilst some boats did use electric power, that source was much more successful in the early model cars, with many multi lane, rail track concessions running from the late 1920s. In the UK, clockwork and rubber bands were the more normal method of powering the cars used for racing, especially with the Cambridge and British Model Car Clubs that both ran regular race meetings. The growth of tethered car racing from the late 1930s in the US was entirely due to the numerous small, IC engines that were becoming available. Several companies also produced casting kits for those that wanted to do their own thing, but this was no longer a necessity, hence the relative popularity of cars. The banning of flying model aeroplanes and ending all official model boat racing during the second war in Britain provided the impetus that established tethered car racing in the UK as there was a large number of engines for which there was no immediate use and numerous enthusiasts that were no longer able to pursue their primary modelling activity.

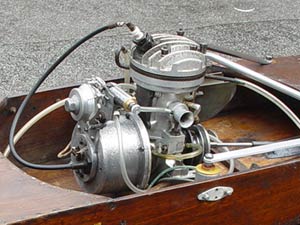

Although Gerry Buck had recorded the first 100mph run with a car in the UK in 1948, this was with a home built engine, as many were at the time, but George Stone pulverised the hydroplane record, causing massive controversy in the process by using a Dooling motor imported from the US. Whilst some stuck resolutely with home built engines, the commercial motors were the route to success both with cars and boats. The Dooling in 5 and 10cc sizes, Hornet and McCoy would be dominant through to the end of tethered car racing in the UK and with the arrival of the Italian SuperTigre and Rossi, well beyond in tethered hydros. Arthur Wall recorded the first ever 100mph run in the UK with a tethered hydro in 1972 using a side exhaust Rossi motor but this was the last hurrah for this style of motor as from 1975 the British record has been held by OPS and later Picco powered boats. The use of commercial and imported motors was met with such antagonism in Britain that both the MPBA and MCA created classes and records that separated the home built and commercial engines in boats and the British and foreign motors and components in cars.

|

|

|

|

| Hornet | Dooling | McCoy | Arthur Wall's 100mph Rossi |

The 40s saw huge strides in engine development, especially in the States where racing continued throughout the war years. The decade started with coils, batteries, magnetos and spark plugs and finished with the ubiquitous glow plug, another American innovation. Britain lagged someway behind, especially with the larger capacity motors, where several manufacturers, large and small, tried to produce engines to compete with the American products. Wilf Rowell up in Dundee, North Downs Engineering (NORDEC), Sid Smith from Chatham (Pioneer), Geoffrey Hastings in Worcester (1066 Products) and Ken Robinson (Speedwell) were just a few of those that produced 10cc motors to compete against the imports. The only real advantage that they held was that of availability, in the light of currency restrictions. With so many American servicemen travelling across the Atlantic, this did not pose too much of a problem for those determined enough. Ultimately, the British motors were never quite powerful enough to beat the imports, but did find willing customers, but not in sufficient numbers to sustain most of the companies.

|

|

|

|

|

| Rowell Mk I | Pioneer IGN | NORDEC Mk I | 1066 Conqueror | Speedwell |

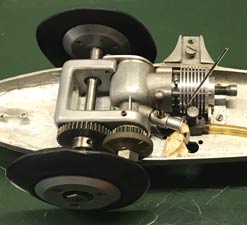

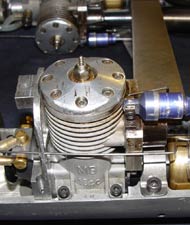

The 5cc class was again dominated by Dooling, although the British ETA found favour with many, especially in hydros, particularly as Ken Bedford of ETA was closely involved in racing and developing the engines, and that they were freely available. It was only in the smaller 2.5cc and 1.5cc classes where the British did make their mark, being internationally successful for many years, and this was almost entirely due to the efforts of the Olivers, father and son, from Nottingham. By the early 1950s, the twinshaft motors and single ended motors they produced, totally dominated these two classes. With the decline of car racing in Britain though, the few concerns that were still in business concentrated on the aeromodelling market, with ETA and Oliver having the same impact on the competition classes there as they did with tethered cars.

|

|

|

| Oliver Tiger MkII twinshaft | Oliver aero motor in spur mount | ETA 29 |

In the mid 1960s, the coming together of a number of engine developments created the style of engine that has been in use ever since in cars and hydros, making what existed up to that time redundant and later, collectors pieces. During the early 1960s Wisneiwski and Theobold developed the use of the tuned pipe with model engines, and such was its effectiveness that since then almost every motor used in tethered cars, hydroplanes and speed planes has used a tuned pipe. The initial problem as far as cars and boats was concerned was that these engines had all been developed for planes, so that the exhaust faced the wrong way, leading to some very odd looking models until manufacturers started producing front exhaust versions or those that could be assembled in either configuration such as the OPS. Oddly, one of the most popular engines in current use, the NovaRossi is still manufactured in rear exhaust form and has to have the hacksaw taken to it and turned round for car or boat use.

|

|

| Rear exhaust Rossi 15 | Rear exhaust OPS 60 |

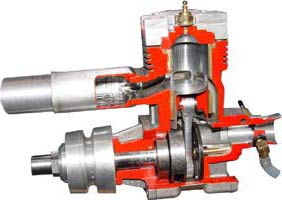

Engines supplied by the late Gualtiero Picco as the 'P' in OPS dominated the 5 and 10cc classes for several years, even after he left to create the Picco factory, which in turn produced almost half the engines in use at any competition. Following his death, remanufactured versions of the 10cc engine power almost every Class 5 car, whilst the OPS and older EXR Picco are still in use in hydros. The motors used today in the other car and hydro classes present an interesting contrast though. Because of the very specialised nature of the sports, apart from the ubiquitous NovaRossi and Picco, most of the engines in use currently are ‘volume home produced’, which does sound a trifle strange. Several international competitors have designed and built their own engines that could compete with the best of the commercial motors, and some have either sufficient manufacturing capacity at ‘home’ or as part of an existing company that allows them to build batches of engines for their own use and for limited sale to others. Stelling in Lithuania, Afanasiev, Kapusikov, Usanov and Soloviev in Russia, along with others, used and sold their own engines. The Kapu and Afa engines have dominated the 1.5cc class for many years, but with the deaths of both Afanasiev and Kapusikov, original spares are unobtainable so that everyone is now reliant on the extensive 'pattern' production industry that exists in eastern Europe.

|

|

|

|

| 10cc OPS sectioned by Steve Poyser | 10cc Picco 8th ed | Reversed NovaRossi 3.5cc | 1.5cc Kausikov |

Although there has been advances in power outputs, the tethered car and hydro engines in use currently have not changed since the late 60s, but there is another power source that is making inroads into all aspects of modelling, and that is electric, and what an impact it has made. Electric classes in hydroplanes have been in existence for a while and have been getting ever faster, yet it was a surprise to all when Oleksi Smolnikov set a new, outright tethered hydroplane record in July 2018 at 146mph, faster than any IC boat. Just eleven months later, Roger Phillips in the US made history with the fastest ever run with a tethered car at over 220mph so the fastest tethered hydro and car in the world are both electric powered. The reason for this is relatively easy to explain and relies on basic physics. The power output of an IC engine is governed by a complex formula and after 120 years of development gains to any of the elements are now marginal at best. By comparison, the power available with an electric set-up is almost unlimited as the output is simply voltage multiplied by current, and whilst the voltage is limited within rules, the amount of current that can be used is entirely down to the available technology being able to withstand the extremes of current being used. For further information on electric power, go to our Electric cars page.

|

|

| Antonio Della Zoppa's Class 5 | The late Roger Phillips' record setting Vector |

As seen previously, there have always been enthusiasts who have preferred, for whatever reasons, to produce their own engines. This may be due to lack of availability, financial constraints, the belief that they can do better than what already exists or just the desire to 'be different'. Many engines produced were almost direct copies of commercial motors, while others went in all sorts of interesting directions, but what they all involved was a large amount of work and complex engineering, along with extensive periods of development if success was to be achieved. To celebrate and record some of this work we are finishing this introduction with a gallery of fascinating engines produced over the years, starting with a panel of 10cc racing engines produced by British enthusiasts.

|

|

|

|

|

| Ted Harris | Dickie Philips | Jimmy Jones | Terry Everitt | John DeMott |

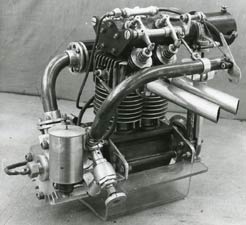

A single cylinder provided a degree of simplicity, but in full sized practice the move was to multiple cylinders and supercharging but this did not translate to model engines, despite numerous experiments. Not every motor is destined to be successful, and there have been some wonderful flights of fancy and engineering exercises that have given builders and other competitors immense pleasure. Many of these engines now rate as collectors items in their own right, such as the supercharged twins of Basil Miles and Bert Stalham and the supercharged two-stroke of John Duffield, that was still being run some 60 years after it was built.

|

|

|

|

| Basil Miles' Barracuda | John Duffield 15cc | Bert Stalham Vee twin | Dickie Phillips twin |

For many years individuals in the Eastern bloc were building engines that were often more successful that the commercial engines, although there have been notable exceptions by enthusiasts from the West. One of the earliest was the Swiss AMRO/FRIRO that was an almost direct copy of the Dooling. Lothar Runkehl specialised in 1,5cc motors that have been ultra competitive from the early 1960s, through to the present day winning European Championships. The late Mats Bohlin won multiple championships with his MB 10s using an exhaust valve, making both the engines and valves available to other racers. Torbjorn Johannessen has used his home built 2.5cc motors that he has developed over a number of years using his own dynamometer set up to win numerous championships recently and break the World and European record in 2016. The superbly engineered 10cc motor was designed by World and European champion Michel Duran in 2014/15 to assess possible improvements in performance to be gained by different transfer channel shaping, achieving a best run 336kph.

|

|

|

|

| Swiss 10cc FRIRO/AMRO | Mats Bohlin MB10 | Torbjorn's 2.5 | Duran/Krasznai 10cc |

©copyrightOTW2022