|

Home Updates Hydros Cars Engines Contacts Links Contact On The Wire Next→ |

|

|

Nordec |

|

This article is a collaboration between Adrian Duncan and OTW. Adrian has published a detailed appraisal of the Nordec in the past where he covered all the technical aspects of the motors. This article is based on that work with OTW undertaking the research into North Downs Engineering Company and the individuals involved. Additional material has come to hand from several sources who are acknowledged at the end of the complete article.

The Nordec 10 cc Motors

During the early post-war years, British power modellers wishing to participate at a competitive level in all-out racing of tethered models, whether hydroplanes, cars or aircraft, faced a common problem - lack of readily-available racing engines. Prior to 1948 such individuals faced a choice between constructing their own engines or somehow contriving to obtain suitable examples from the USA, where development and manufacture of such power plants had resumed at a rapid pace following the conclusion of WW2.

This began to change in 1948, when a handful of British manufacturers threw their hats into the racing engine ring more or less simultaneously. Elsewhere on this site we have presented information on two of these, the Rowell and Ten-Sixty-Six ventures. Here we’ll focus on the third British racing engine series to appear in 1948 - the Nordec 60 models.

Background

The Nordec Motors were unveiled to the public at the Model Engineer Exhibition in August 1948, with the 'first production motors scheduled for delivery later that month'. Prototypes were being flown for a considerable time previous to this though, and with remarkable results, as perusal of contemporary magazines shows. The launch of engines was also covered in most model aircraft and model car magazines in August 48, noting that they were being produced by 'North Downs Engineering'. Just what was the connection between that company and a range of 10cc racing motors though?

The origins of the Nordec motors lie in two companies formed by Leslie Ballamy, a renowned engineer probably best known for his work on suspension systems for cars and after-market performance parts. In 1939 he moved his business to Wapses Lodge, part of an old army base on the Godstone Road at Whyteleafe in Surrey. The premises he grandly named ‘The Research Laboratory’, naming the company ‘L.M. Ballamy, Consulting and Experimental Engineers’. Inevitably, war work soon occupied the design and production facilities, but this was not Ballamy’s prime interest, which was of course, cars. To this end, he took over the ‘Westway Garage’ on the Chaldon Road in Caterham, sometime in the early 1940s. This became ‘L.M. Ballamy, Motor Engineers’.

Ballamy was exceedingly well known in the world of car racing and providing design solutions, even for manufacturers, taking out numerous patents during the course of his career. However, Ballamy was not the owner of either of these companies, as the money behind them came from Major Richard Sheepshanks, a wealthy Suffolk landowner and businessman from Eyke, near Woodbridge. As the owner, Sheepshanks appears as co-patentee on many of the patents that were filed, leading Ballamy to consider that the ‘Major’ was getting rich at his expense. This resulted in an almighty row, culminating in Ballamy resigning from the company in the middle of 1946. Not only did he leave the company, but also more significantly, he took a number of key designers and engineers with him.

With Ballamy no longer involved, the businesses were reorganised as North Downs Engineering Co, still working from the Research Laboratory and the Westway Garage. Marcus Chambers became general Manager and Ken Roberts chief designer. The company continued supplying supercharging kits, as well as retaining the rights to some of Ballamy’s patents. It was during this period though, that the one and only ‘Nordec’ car came into being, but with Sheepshanks unwilling to divert money for development, this project was stillborn.

A further series of blows to the company occurred at the end of 1947, firstly with the departure of a number of engineers, who formed Wade Superchargers in December of that year, followed soon after by the Chief Designer and then Marcus Chambers, the Manager. This difficult situation was compounded by regulations regarding use of materials and manufactured items, which had not only put paid to the planned new factory on the Wapses Lodge site, but were directing industrial production towards exports, presumably leaving North Downs Engineering with surplus capacity.

The last member of the senior staff remaining at the company was Works Manager John Wood, and he is the key figure in the development of the Nordec range of engines. Along the way, he seemed to have inherited the position of Chief Designer of the company as well as running the works. In addition, and far more significantly, he was also a member of the Croydon and District Model Aircraft Club and involved in the rapidly developing sport of speed control line flying. Here existed an ideal opportunity for John Wood to design, and the company produce, a motor for him to develop and prove in competition as well as provide export potential for North Downs Engineering.

The practical challenge of getting North Downs new manufacturing effort underway was doubtless eased by the fact that from the outset they were well-equipped with precision machine tools, so the necessary investment in machinery had already been made.

Sheepshanks had already demonstrated his unwillingness to inject further cash for development and with John Wood no doubt being fully aware of the already successful American motors it would seem reasonable that rather than designing and developing a motor from scratch, the company would look across the Atlantic Ocean to find a proven prototype on which to base their new 10cc motor.

This was of course the 1946-47 version of the highly successful McCoy 60 Red Head racing engine, which was then in full-scale production by the Duro-Matic Products Company of Hollywood, California. The McCoy was already well established as a design to be reckoned with in the highly competitive performance fields of control line speed and model car racing.

Seeing no need to re-invent the wheel, North Downs quite logically took the line of least resistance by unashamedly 'borrowing' the majority of the design features of their new offering from the McCoy model. This allowed them to get their new product into series production very much faster and less expensively than would have been the case if they had had to develop their own design from the ground up.

North Downs were not alone in taking this approach. All three of the British 10cc racing engines which appeared more or less simultaneously in 1948 were quite understandably influenced in one way or another by then all-conquering American designs. The Ten-Sixty-Six Conqueror embodied a blend of American and home-grown Westbury features, while the Rowell 60 exhibited a mix of trans-Atlantic Hornet and McCoy influences. The Nordec, by contrast, was more or less directly based upon the then-current McCoy 60 model.

The ignition issue

At this point, it’s important to recall that in early 1948 when the original Nordec designs were evidently being finalized, the contemporary McCoy was not the later all-conquering Series 20 model which appeared later in 1948 but was still the spark-ignition 1946-47 Red Head 60 with black-anodized case, red head, rear disc valve induction and by later standards, relatively restricted porting. The designer of the Nordec clearly took a long hard look at this version of the McCoy and based his design very much upon that motor. However, he did introduce a number of changes of varying effectiveness.

One factor requiring consideration (which McCoy was even then in the process of evaluating) was the issue of the ignition system. During the period when development of the Nordec was in progress, the glow-plug had only just been refined by Ray Arden into its commercial form in the USA, and at the time of the Nordec’s release in 1948 modellers were still divided on the subject of whether or not the new form of ignition was in fact superior in strictly performance terms, particularly for all-out competition applications. The very precise ignition timing adjustment permitted by the use of an adjustable timer was a factor which many saw as a performance advantage of the spark ignition configuration, although the elimination of the weight penalty of the spark ignition system was of course widely recognized as a major benefit of glow-plug ignition.

However, the weight penalty of the spark ignition components was very much less of a factor in relative terms for the large and heavy 10cc racing engines of the day. In particular, the applicability of such engines to car and hydroplane purposes was far less adversely impacted by weight considerations than it was for model aircraft use. Accordingly, many racing competitors of the day stuck with spark ignition for some time following the introduction of the glow-plug. As events were to prove, the glow-plug was destined to sweep the spark ignition engine aside and become the standard very quickly. Sixty years later, it’s all too easy to forget that this was not yet obvious in 1948.

|

Regardless, the rising interest in glow-plug ignition was not lost upon British accessory manufacturers, and a reliable indication of the rapid development of a demand in Britain for glow-plugs may be derived from the fact that by the end of 1948 no fewer than three British firms were engaged in the manufacture and/or marketing of glow-plugs. The first and most significant of these was the large and well-established automotive firm of Smith’s Motor Accessories Ltd, who found it economically worthwhile in mid 1948 to have their subsidiary K.L.G. Sparking Plugs Ltd. commence production of the famous 'Miniglow' plugs in various sizes. These were to become something of an icon in British modelling circles and were destined to remain on the market for several decades. |

|

|

|

In his January 1949 book 'Model Glow Plug Engines', Col. C. E. Bowden reported that as of late 1948 British-made glow plugs were also being offered under the McCoy Hotpoint label as well as by the then-emerging firm of Keil Kraft. The actual manufacturers of the latter two plug brands are unclear at this distance in time. L-R: KLG Mini spark plug, Champion VG glow, KLG Miniglow, McCoy Hotpoint |

All of this clearly highlighted glow-plug ignition as an emerging factor in the British modelling scene that could not be ignored by a new manufacturer wishing to start off on a forward-looking basis. Consequently, the Nordec 10 cc racing engine was introduced from the outset in both spark ignition and glow-plug versions. Nordec actually appears to have been ahead of McCoy in this respect, since the production glow-plug version of the Series 20 McCoy 60 did not appear until 1949. Interestingly enough, recorded serial numbers prove that both the spark ignition and glow-plug ignition models of the original Nordec remained in production concurrently throughout the engine’s admittedly short production life, indicating that there remained a market niche for the sparker even after the introduction of the glow-plug model.

The early Nordecs

The two models which resulted from the design approach described above were designated the Nordec R10 (spark ignition) and Nordec RG10 (glow-plug) respectively.

|

Nordec R10 ignition |

These were identical in almost all respects, the only real differences being in the front housings. McCoy influence was immediately apparent in the engines’ bore and stroke measurements - 0.940 in. and 0.875 in. respectively for a displacement of 9.95cc. The retail price of the original Nordec models was a whopping £12 10s 0d (£12.50) for the spark ignition model and £12 for the glow-plug version. Left: Drawing of R10 by C Sherratt in Lawrence Sparey's 1949 'Model Cars' analysis |

|

|

Nordec RG10 Glow |

The very sturdy sand-cast crankcase with integral exhaust stack, detachable front and rear housings and durable black finish on its un-machined surfaces were also direct parallels with the McCoy. In addition, the mounting holes were identically spaced, meaning that the Nordec and McCoy were directly interchangeable in the same model. Perhaps Nordec were entertaining heady visions of making a few converts both at home and abroad? Left: Drawing of RG 10 by Bagley in Lawrence Sparey's 1949 'Aeromodeller' test |

|

Although the induction, twin ball-race crankshaft support, bypass arrangements, cylinder porting, piston design and timing were all more or less identical to that of the 1946 McCoy, there were some differences. Firstly, unlike the McCoy, which was a single piece crankcase, the cooling fins on the Nordec were machined separately, probably for ease of manufacture. This required six long cylinder head screws that passed through the fins and were screwed into the lower half of the crankcase. Most notably though, the cylinder head design was far less sophisticated than that of the McCoy. The plain aluminium alloy cylinder head of the original Nordec is not a casting as used in the McCoy but instead is machined from solid bar.

|

This has one rather unfortunate effect - it presents a significant production challenge in connection with the contouring of the underside of the head to match the somewhat complex piston crown, given that the ideal shape is significantly asymmetrical. And indeed no attempt was made to create a matching shape and hence a more efficient combustion chamber. The underside of the cylinder head was simply turned into a bowl shape with a narrow and clearly ineffective "squish band" at the edge and a broad slot milled across at the appropriate point to provide baffle clearance. This head conformed only marginally to the piston crown, and the resulting inefficient low-swirl combustion chamber with numerous "gas pockets" was one of the Achilles heels of the Nordec in performance terms, as events were to prove. |

|

There were two distinct head configurations available for the Nordec. Externally, these appeared identical. However, the combustion chamber "bowls" of the two head types were cut to different depths to give a choice of compression ratios. The low-compression head (around 8:1) naturally had a deeper bowl machined into its underside to increase the combustion chamber volume at top dead centre, and this had the effect of reducing the head thickness available for the plug threads. Consequently, the low compression head was intended for use with a shorter-reach plug than the high compression version. The low compression head is externally identified by having a letter "S" stamped into the horizontal surface of the plug recess. The high compression head (approximately 10:1) is externally unmarked.

|

The rest of the cylinder/piston/rod set-up is more or less similar to the McCoy, down to the sturdy forged con-rod with bronze-bushed big end and nominally-identical working length between centres. WW code indicates that, as well as the pistons and rings, the rods were also probably supplied by Wellworthy who were supplying similar components to other manufacturers at that time. |

|

|

For the other major difference, we must look to the front end assembly. Here we immediately notice one production change of some significance - the Nordec crankshaft is a built-up item rather than a one-piece item as used on the McCoy. The crankweb is a separate component which is press-fitted onto the crankshaft. This can be clearly seen in the comparison view of the McCoy and Nordec crankshafts, as can the different shape of the counterbalance portions of the two crankwebs. |

|

So the Nordec certainly borrowed a great deal from the McCoy, but it does show evidence of a certain amount of original thinking, if only in production terms for the most part. The engines are beautifully made throughout, with fits of the highest order and high-quality steel Allen-head screws used for assembly.

|

|

The screws used were the renowned 'Unbrako' brand and for a while the Unbrako company used the Nordec motor in their adverts. The sand-castings are a bit rough-surfaced, but certainly well up to the job. Overall, these are very well-made engines which should give excellent service. Left: Unbrako Allen screws from Nordec. Right: Phillips crossheads as used in American motors |

Edgar Westbury confirmed the quality of the engines in an article in Model Engineer in December 1948 following a visit to the factory. He said "I can now say without hesitation that the engines are a conscientious job, produced from good and suitable materials, by sound machining methods, to limits of accuracy which are at least as high (to my certain knowledge) as those observed in the standard productions of some of the most highly reputed foreign engine manufacturers." The article included the following photographs of operations at the factory including the assembly bench where at least 22 motors can be seen.

|

|

|

|

| Honing cylinder bores with a Delapena mandrel |

Grinding crankshaft journals | Jig drilling a piston | Gang milling cylinder head fins |

|

|

|

| Surface grinding piston rings | Machining flywheels | Engine assembly (22 motors on bench) |

Part II: Performance and test, so how did they work in reality?? Let’s find out ………….

The tragedy of the Nordec (if it deserves that term!) is that it was in effect copied from a prototype which was in the process of being drastically upgraded at the very time when North Downs were first getting their engine onto the market. As a result, its performance was immediately overshadowed by the vastly improved Series 20 version of the McCoy 60 which was introduced in 1948. The same fate of course befell the competing Rowell 60 and Ten-Sixty-Six Conqueror.

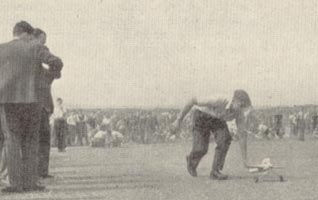

As far as the British press was concerned, the Nordec got off to a very promising start. At the Northern Heights Gala at Langley Aerodrome in June 1948 John Wood with his RG10 powered speed model made a demonstration flight watched keenly by the then Queen Elizabeth and Princess Margaret. This also confirmed Wood's involvement with the development of the Nordec with 'Flight stating', " The Queen and Princess were given a demonstration of control line flying by J.B. Wood, whose company North Downs Engineering Co, are starting production of the only 10cc two stroke model power unit to be made in this country."

John and his plane were presented to Her Majesty so that he could explain speed flying and the style of model to her. According to 'Flight' 'The Queen was obviously amazed at the display and expressed pleasure in learning that the Nordec engine, with which the model was powered, is to be produced in quantity for export.' John and his 'Racer' design also went on to win the speed event at the West Essex event, setting the inaugural British Class D record at 95.3mph. A film clip of Wood’s flight can be viewed on the British Pathe site (link)

|

|

|

| John Wood is presented to HM Queen Elizabeth at the 1948 Northern Heights Gala at Langley Aerodrome | ||

Col. Bowden made much of the engine in his previously-mentioned book on glow-plug engines, stating that the engine filled "a long-felt want in this country". He praised the quality of construction of his own example, and in this at least examination of surviving examples fully bears him out. He reported using his Nordec in a 44 inch long high-speed boat, an illustration of which appeared in the book. Finally, he noted that in 1948 the Nordec had established a British control-line speed record in its class at a 'shattering' 95.3 mph. Nothing there to make Dick McCoy, Ray Snow or Tom Dooling choke on their coffee, but there were few McCoys, Hornets or Doolings in Britain at the time for the Nordec to compete with. Just as well, perhaps …………….

|

Following the release of Col. Bowden’s book, the RG10 glow-plug version of the Nordec was tested by Lawrence Sparey, the test report being published in the March 1949 issue of 'Aeromodeller' magazine. This was in one respect a historic test - it was the first-ever test by Sparey of a glow-plug model engine. This illustrates the fact that interest in the glow-plug engine in diesel-minded Britain had lagged well behind that in the United States, where the glow-plug engine had been all the rage for well over a year prior to this date. Right: John Wood starting his 'racer' with the 'Nordec Starter' |

|

|

For a first test of a glow-plug engine, things went very well and Sparey was unstinting in his praise for the engine. He characterized starting as 'exceptionally easy' and running qualities as being 'free from all fussiness'. As a Nordec user myself, I would endorse both those comments. Sparey praised the engine’s response to adjustments of the needle, while commenting also on its prodigious thirst!! He referred most favourably to the quality of the engine’s construction and summarized its performance as 'excellent, if not remarkable'.

The latter statement must be read in the context of measured performances of other contemporary British models. It has to be said that performance standards for British glow-plug engines at the time generally lagged well behind those in America. The Nordec was entirely typical in this regard and hence was little if any worse than many other contemporary British glow-plug engines in terms of its specific output.

|

The actual peak power measured by Sparey was only 0.48 BHP at 11,200 rpm using a straight 75-25 percent fuel mix of methanol and castor oil. No doubt things would have improved substantially if a proportion of nitro-methane had been added. Even so, this could scarcely be classified as a true 'racing' performance! Regardless of the reason, there’s no question at all that the Nordec failed to approach the performance of the McCoy original. Even the 1946 version of the McCoy reportedly developed a measured power output in the order of 1.0 BHP at around 13,000 rpm (admittedly using nitro), and the Nordec certainly didn’t approach these figures. And to make matters worse, the Series 20 McCoy 60 introduced in 1948 more or less concurrently with the original Nordec performed at a far higher level than its 1946/47 predecessor upon which the Nordec was based. In essence, the Nordec was out of date in design and performance terms as soon as it was released. Nordec RG10 at left and McCoy Series 20 stripped for comparison |

|

Not to be outdone, 'Aeromodeller’s' rival British magazine 'Model Aircraft' published a test of both the R10 and RG10 models which appeared in its June 1949 issue. Although the latter test was unattributed, it was almost certainly carried out by Peter Chinn. A slightly superior power figure to that obtained by Sparey was recorded, the published figures being just over 0.6 BHP at 12,000 rpm on glow-plug. But this more or less confirms the fact that the Nordec in its original form was a less than stellar performer by comparison with its competitors. That said, there’s no doubt that the original Nordec was (and is) a very nice engine to handle, especially for such a large unit.

|

|

Despite the use of a surface jet needle valve set-up, suction is actually quite reasonable, doubtless due to the relatively small venturi section used consequently, the Nordec was used in applications which stretched well beyond those normally expected from a racing motor. Significantly smaller venturi and disc cut-out of the Nordec on right compared with the S20 McCoy on left. McCoy also uses die cast disc rotor. |

Despite its rather excessive weight, it was actually used in large control line stunt models by a few deaf modellers with deep enough pockets to afford the fuel bills, and its running characteristics were surprisingly well suited to this application, particularly if a spraybar was fitted in place of the surface jet system.

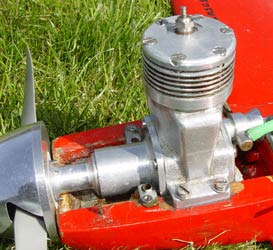

But the Nordec had of course been intended all along for racing applications, and its natural métier was the control line speed model, although it was also tried out in the then-popular sports of tethered hydroplane and model car racing as well. North Downs offered a well-made flywheel and clutch set-up for use with the engine in a racing car application, and an aluminium spur drive mount from August 48, either as a finished unit or as castings. However, it seems that the Nordec was at best an indifferent performer in both of these applications and was largely ignored by the hydro and tether car competitors of the day. It certainly never achieved any real success in either of these fields.

|

Despite this, the Nordec continued to attract some interest from among the aeromodelling community, receiving some attention from the tuning experts who were an evolving breed at the time. Indeed, a Nordec was one of the first engines that the legendary tuner Fred Carter had a go at re-working, in order to get more out of the motor than its original configuration allowed. The results of his efforts were quite tangible. At a time when the stock engine was good for perhaps 100 mph under ideal conditions, Carter’s Nordec-powered 'Little Rocket' consistently turned in speeds of around 116 mph, a fine performance by then-current British standards. This success marked the beginning of Carter’s long run of pre-eminence as a racing engine tuner in Britain. Happily, the 'Carter Nordec' motor is still in existence, although not in the original 'Little Rocket'. |

|

|

|

|

However, Carter’s performances paled beside those of the renowned Czech expert (and founding director of the MVVS organization) Zdeněk Husička. Having somehow, from behind the Iron Curtain, obtained an example of the Nordec 60, Husička achieved a speed of 129.56 mph at a contest in Brno in September 1952 using this engine. As far as I’m able to determine from the records currently at my disposal, this was the fastest speed ever officially recorded by a Nordec in competition. The engine was most likely one of the very rare Nordec Special Series II models to be described below - surely no-one ever got the original Nordec to go that fast!?!

Further development of the Nordec

With Wood being so actively involved in speed flying, he would have been well aware of current design trends and development as well as the inadequacies of the original combustion chamber design. In late 1949 a revised head design was produced to address this issue. The new head was a casting instead of the machined unit formerly used, and this allowed the provision of a combustion chamber contour which more correctly matched that of the piston crown, thus eliminating the problem of 'gas pockets', promoting improved swirl and hence improving combustion efficiency.

|

|

|

| New Nordec head | Compared with McCoy on left | Much larger ports in McCoy on right |

|

The company released an updated version of the engine designated the 'Nordec Special' in December of 1949, still in both glow and spark ignition forms. This was more or less identical to the earlier models with the exception of the revised cylinder head. However, the somewhat restrictive porting and induction system remained unaltered, and in consequence the performance of this version still lagged far behind that of the now all-conquering Series 20 McCoy Red Head 60 and Dooling 61 designs. As a result, the original Nordec Special can hardly be termed a success in performance terms. The marketplace evidently agreed with this assessment, and sales were not brisk. Right: RG10 MkI Special Series I. Often wrongly described as a MkII |

|

©copyrightOTW2012