|

Home Updates Hydros Cars Engines Contacts Links 1066 History 1066 Cars Contact On The Wire |

Ten Sixty Six Products: Engines

|

|

|

|

|

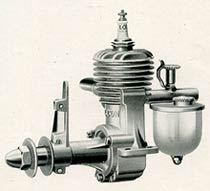

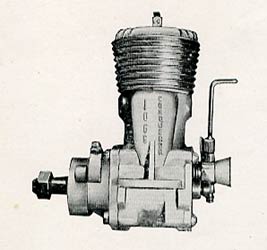

Falcon:

The Falcon was the first engine to be produced by 1066 and initially offered in 5cc, 10cc and 15cc size. Early adverts give the specification and price for the 5cc and 10cc versions, but no further mention is made of the 15cc. The Falcon 1 was produced extensively, but the Falcon 2 does not seem to have made it into production, although the dies were obviously made as two casting sets and some spares have turned up in the last few years. The 10cc Falcon 2 looked similar in every respect to the Falcon 1 but was physically bigger. The only visible difference between the two motors being the angled spark plug on the 2. The 15cc version may only have existed as a prototype, if at all.

|

|

The Falcon was a conventional sideport, spark ignition motor with a plain phosphor bronze bearing, and suitable for home building with a distinct family resemblance to other Edgar Westbury designs. The Falcon 1 has bore of 3/4" and stroke of 11/16" that gives a capacity of 4.97cc. The crankshaft was supplied ready made and although a bit flimsy at ¼"dia was completely plain. Another Westbury feature was the split collet that slipped over the crankshaft, with the contact breaker cam on the inboard end, a taper to lock into a flywheel or prop driver and a parallel portion, which was threaded. This system was also used on all subsequent 5cc engines and enabled the same crank to be used, both for cars with a long collet and for planes with a short collet and prop driver. The longer collet had an extended ¼ inch dia nose for a clutch drum to run on. A plain lapped piston with a very small deflector ran in a hardened steel liner. |

The crankcase was a single casting with a bolted on front housing and cylinder head. Two screws held on a separate exhaust stub. The contact breaker assembly was mounted on a short parallel portion of the front housing and rotated to alter timing. The contact breaker arm is a large casting and quite complex. The moving point is controlled by a fibre pin, which runs in this casting, but also goes through an enlarged hole in the front housing. Any attempt to remove the CB assembly without first removing this pin will result in frustration and serious damage. The underside of the crankcase had ‘Westbury style’, cast in cooling fins, (somewhat unnecessarily one feels given the power of these motors). Webs give the very thin mounting lugs a bit of reinforcement. The venturi and top of the fuel bowl was a one piece casting with a split needle valve assembly.

It has yet to be confirmed if the ‘factory’ produced any completed engines for sale and so far, no Falcon with a serial number has yet surfaced, yet the box below may be the evidence of the Falcon having been sold as a complete engine in the very early days of 1066 as it is marked Falcon 1 5cc.

|

|

|

The Parts Kit

|

These engines were available as a kit in a partitioned cardboard box complete with drawings, or in various stages of completion. The kit was originally 24/6 (£1.27). Falcon 1, 5cc kits and engines are still fairly common and do not command great fortunes. The Falcon 2 is very rare and at present only two examples of this version are known to exist built from castings sets found at autojumbles. Judging by the number of part finished engines and kits that have appeared, the home build concept of the engine proved beyond the capabilities of many of the purchasers. There exists a wonderful selection of incorrectly and badly machined components, including some fairly disastrous and basic errors. Two different boxes for the Falcon kit have been found, this one being a later version with a yellow logo. |

|

The Falcon 2 displayed at the 1946 Model Engineer exhibition had the cylinder head somewhat oddly with the fins across the engine, believed to be a die making error. Of the two examples that exist, one has followed this exactly whilst the other has placed the fins fore and aft, which required altering the combustion chamber inside the head.

|

|

| The only two Falcon 2 10cc versions known to exist. | |

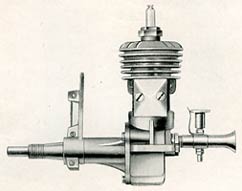

5cc Hawk:

The 5cc Hawk is the engine shown fitted to the MRC car in all adverts and the 1066 catalogue. It is loosely based on the earlier Falcon design, with many parts being interchangeable. To add to the confusion slightly, it is wrongly captioned as an Arrow in Mr Clanfords A-Z, an error that has been repeated regularly. The most obvious differences between the Falcon and Hawk are the separate screwed in Cast Iron barrel and the change to a rear disc valve induction. These changes required new set of dies for the crankcase as well as patterns and cores for the cylinder.

|

|

The basic design was similar to the falcon, but the crankcase was altered to accommodate the new separate barrel with a venturi boss being added to the rear face. The barrel was new, but relatively low tech, and to ease the casting and machining of the ports reverted to a separate transfer cover. A ground and honed cast iron piston ran directly in the iron cylinder.

The front housing, contact breaker assembly and head were all

interchangeable with the Falcon. As the cylinder screws into the crankcase it

required very accurate machining to ensure that the cylinder lined up exactly

and then both were drilled and a pin fitted, half in the case and half in the

cylinder. This is one sure way of telling if the engine is a 1066 original or

made up from parts.

Because of the restrictions on industry

that existed at the time, the engine was initially only available for export,

but by Nov 1948 was made ‘available to the home market’. |

|

The Hawk was available in 2 versions, H/RC for cars and boats, H/A for planes. Both featured a simple trumpet shape venturi with a two-part spray bar screwed into an enlarged centre section. For aeroplane use, a clear plastic tank with an aluminium top was attached to the underside of the venturi using a small bracket and brass draw bolt. A long choke tube replaced the fuel nipple. The H/A version intended for planes had a standard Falcon style crankshaft whilst the car and hydro model had a hardened and ground full circle version, specially designed to ‘improve the volumetric efficiency of the crankcase’. Westbury designed his engines with very low crankcase compression, as he reasoned that overcoming this compression reduced the power of the engines. How wrong could he be? The change from sideport to RRV induction and reduction in the crankcase volume must have increased power noticeably. |

|

Adverts for the MRC car in the 1066 catalogue show a Hawk with a CL2 clutch fitted to the chassis, and this is probably where most of the engines were used.

|

Contemporary evidence suggests that the Hawk was only in production for a year and then only available as a completed factory built motor at £6.10.00 (£6.50). For this reason the engine is not very common. Engine numbers started at 1000 with the highest so far noted being 1032. A few motors have been built from spare parts to add to the total but probably no more than 50 Hawks exist. By coincidence the first production Hawk,

serial# 1000, with a three-shoe clutch fitted was

offered for sale on eBay during 2005, discovered near Worcester

where it had been purchased personally from Geoffrey Hastings. |

|

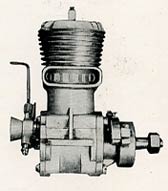

10cc Conqueror:

The Conqueror was developed during 1948 and at last reflected the then current design trends for the larger sized racing motors. Adverts for the Conqueror were gushing in their praise for the new engine. "A high performance precision built British racing engine" was "a real record breaker", an "amazing engine". The reality however was somewhat less spectacular.

|

|

|

| Artist's impression | Original, factory built Mk I | |

A full 10 cc, the Conqueror was similar in layout to a whole host of other contemporary products. Elements of ‘Westbury influence’ were still evident in the design. The crankcase consisted of three die-castings. Centre section with large cast in transfer and exhaust ports, a twin ball bearing front housing, a rear housing with the disc valve and a threaded hole for the venturi. The two housings were spigotted into the crankcase and held with four screws each. The cooling fins were relatively small and had to be machined from the solid casting using a form tool that gave them a ‘rounded’ appearance. A finned, cast head topped off the cylinder whilst a ringed aluminium piston, with a large deflector, ran in a spun cast iron liner. Both rings and liners were supplied by Wellworthy. Up to 6 exhaust and 6 transfer ports occupied most of the circumference of the liner.

The crankshaft in the specification and illustrations is tapered for a prop driver or flywheel, yet most engines seem to have a parallel shaft, which has been reduced to 5/16" for a collet. Both types of shaft were threaded 5/16" BSF. The drawings supplied with the kits show the parallel shaft rather than the tapered version.

The Mk 1 motor had a straight venturi similar to the Rowell Mk1 and McCoy. This was threaded and then locked into the backplate with a knurled brass locking ring. The needle valve assembly is interchangeable with those on the Hawk and Arrow engines despite the difference in capacity.

The contact breaker assembly was compact but complex. The moving points were mounted on a swinging arm that was pivoted at one end and secured at the other to a conventional split clamp with a minute screw. This arrangement was to allow the moving point and cam follower to swing out of the way so that the CB assembly could be removed from the front housing. Again, attempting to remove the clamp without first swinging the arm out of harms way would result in a frustrating and damaging experience. The contact breaker cam was machined onto the shaft rather than being on a collet as on previous engines. A glow version of the motor was also available.

Initially the Conqueror Mk 1 was supplied boxed, "tested in excess of 20,000 rpm" and ready to run, with spark plug for £8.5.0 or £8.2.6 for the glow version. A whole 12p less! It was claimed that the motor, untuned, would exceed 23,800 rpm when run in.

After a short while the Company ‘reacted to demand’ and supplied a casting kit similar to the Falcon and Arrow engines. Again, many of the components were supplied already finished but the crankshaft had to be obtained separately. The kit retailed at £2.17.6. Factory built Mk 1s had serial numbers running from 500 with the still NIB # 644 being the highest number so far discovered.

|

|

|

| MKI #644 still new and with the only original Conqueror box known to exist | Very rare Conqueror kit | |

An updated version of the Conqueror appeared sometime in 1949. There does not seem to be any reference to this development in adverts or ‘jottings’ in the various magazines. The engine is not as illustrated and identified in Clanford’s A-Z as a MkII. The most obvious way to distinguish the two marks is from the bypass, which is still tapered, but increased in size on the MkII by a full 1/8" to 1" exactly. The alterations were to the original dies and can be clearly seen on some of the examples examined. There does not appear to be any change in the port sizes with the exhaust still half the circumference of the liner. The increase in size was probably intended to even up the gas flow to the transfer ports. There seems to be no discernable difference in size of the venturi either, which is still straight.

|

The kits do not seem to give any indication of which mark the motor is and the drawings show no differences in dimensions. There seems to be almost equal numbers of home constructed MkIs and IIs in existence. Factory built MkII engines are rare however. These were numbered from 200 with 285 being the highest number so far discovered. There has been a surge of interest in the Conqueror engine recently and over 30 examples of the various Marks have appeared for sale in the last three years.

There is some evidence that

the Conqueror was developed yet further in the last few months of the company’s

existence. Photographs show examples of engines fitted with ‘downdraught’

venturis but quite where this development fitted in was a bit of a mystery until

the ‘Mk II’ illustrated in Mike Clanford’s A-Z turned up at a swapmeet. The

backplate on this motor carries a very clear MkIV that has been stamped into the

die. The venturi bore is 3/32" larger than standard at 13/32". |

|

The rest of the motor is standard MkII however. Whether this was a factory upgrade made available for existing motors or one of the ‘exciting new developments’ noted during a visit to 1066 remained a mystery until an engine was discovered in a factory built Conquest car that was obviously very different to the earlier Mks. The crankcase casting had a cylinder and head much larger in diameter than previously with the bypass also enlarged quite considerably. Was this the MkIV Conqueror, but if so, why was the downdraught venturi not fitted and what was the reason for retaining the spark ignition? Another similar set of cases for this engine have been around for a while, but more importantly, another complete engine turned up in 2021, this time with the MkIV downdraught venturi fitted, although still with spark ignition. Evidence of the existence of the MkIV begs the question of whether there was ever a MkIII and so far nothing has emerged that would indicate this mark having been introduced.

|

|

|

| Downdraught MkIV backplate | Factory prototype MkIV | MkIV as planned? |

The Conqueror was competing with the British made Nordec and Rowell engines as well as the imported McCoys and Doolings and in spite of the extravagant claims was never able to match these motors for performance. The low price and availability as a kit seem to be the prime reasons for the relatively large numbers sold. It has powered planes, tethered hydros and cars in a variety of forms. Bob Thomas of the Midland Club even fitted a supercharged version to one of his highly modified Conquest cars.

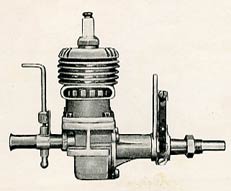

5cc Arrow:

The Arrow was probably a last attempt to compete in the market for 5cc B class engines. It looked more like other racing engines from that era and showed a marked ‘American’ influence, looking like a baby Hornet in many respects. Bore and stroke were the same as the previous two engines. The cylinder, however, was now a separate aluminium casting with a square four-bolt flange, which mated to a similar flange on the crankcase, which was in all reality, still a Hawk.. The exhaust port and stub had grown dramatically compared with the Falcon and Hawk and was now a full 180 degrees of the cylinder circumference.

|

|

The use of an aluminium barrel necessitated a return to an iron liner. The liner was in spun cast iron supplied by Wellworthy. A ground and honed iron piston was fitted as standard but an aluminium piston with rings supplied again by Wellworthy was available as an option. The transfer passage was now cast and machined into the cylinder. Again RRV induction, the Arrow shared many other components with the Hawk and Falcon. The rotary valve was a steel disc with a shouldered pin, which engaged with a hole in the crankpin The crankshaft specified was the full circle version as supplied for the H/RC Hawk. The venturi was also the same design as used for the Hawk although the needle supplied was now a simple bent wire type. As was often the case with products from the company, a design ‘glitch’ meant that with the needle valve assembly vertical as for the car installation the setting could not be adjusted as the needle fouled the cylinder when turned. |

Following on quickly from the Hawk, the Arrow, although continuing with the family resemblance, required another modified set of dies for the crankcase and an entirely new set for the cylinder. The adverts proudly claimed that these dies were produced in the 1066 works.

|

Like the Falcon, the engine was supplied as a casting kit, but at the increased price of 33/- (£1.65) and included a finished venturi and needle assembly with all necessary hardware and drawings to complete construction. The crankshaft had to be obtained separately from stockists at a cost of 14/6. No evidence has yet come to light that any Arrows were built or supplied by the factory. All this amounted to a motor billed by the factory as ‘A Record Breaker In The 5cc Class’, but it is questionable whether all these changes had added much in the way of performance to the basic layout. Originally rated at 0.3 bhp. the Arrow was now competing against the ETA 29 and several other high performance 5cc motors, which were producing in excess of 0.6 bhp, so again sales were very limited. Along with the Hawk this motor remains a very rare item indeed, although a couple of complete engines, two boxed kits and other spare parts have turned up at swapmeets and on eBay in the last few years. |

|

Thanks to Eric Offen, Miles Patience, John Goodall, Ken Butterfield and the late Dick Roberts for items and images

©copyrightOTW2021