|

Home Updates Hydros Cars Engines Contacts Links 1066 Cars 1066 Engines Contact On The Wire |

Ten Sixty Six Products of Worcester

|

|

|

|

The catalyst for an article and associated research for OTW usually starts with items, or information that have not been recorded elsewhere and represent the more enjoyable, if sometimes frustrating aspect of publishing the website. Most commercially produced cars or engines are more than adequately dealt with in numerous specialist publications from the 40s and 50s, but along with the late lamented MEW magazine, MEN website and the great work Adrian Duncan is doing we do like to present the context, background, and people that were involved along the way.

The great advantage of a website is that material can be added at any time and any errors or falsehoods corrected. Some projects are straightforward while some take huge amounts of work and still continue to evolve. Such was the case with one of the earliest manufacturers we featured, Ten Sixty Six Products of Worcester.

|

Possibly because they were plentiful and cheap I became an enthusiast for the products of this company, which seemed, at that time, to be very underrated, and had been trying to gather together a representative collection of their products, made somewhat easier by a large quantity of unused items that were appearing and rumours of a similarly large hoard ‘somewhere in Kent’. Intrigued by all these items that were surfacing and fascinated by the stories that I had heard about 1066, I set out to record, as far as possible, the activities of the company which had been right at the forefront of commercial model car and engine production during the heyday of tether car racing. Thanks to the extensive advertising and marketing, there was no shortage of information relating to their products, but what became quickly apparent was the almost total lack of any hard evidence about the Company or its principal, a Mr G.I. Hastings. Having completed my research into the products it became clear to me that the story was still only half finished, I knew very little about the Company that had produced these items and that, with the exception of a few unsubstantiated rumours, neither did anyone else have much of an idea either. |

|

|

|

The Company’s first advert appeared in February of 1946 and these continued for the next four years when the last of their adverts appeared in the specialist magazines. Just as mysteriously as the adverts had ceased, so the company seemed to disappear without further mention. Several retailers continued to advertise products from the company for many years, but of Ten-Sixty-Six, there was no further trace. What had become of such an active company?

|

|

The Battenhall Road address in the adverts seemed a realistic place to start, but as this was now a private house there was nothing further forthcoming at this stage, I turned my attention to Mr Hastings. Although initials and surnames were the normal method of address in the 40s Christian names could often be found in reports or gossip columns such as Dope and Castor. In every reference Mr Hastings was given the full title of G.I. or Mr Hastings, but at no stage was a Christian name mentioned which might give a positive identification. An additional complication was an indication from several sources that Hastings was not even his real name. I was becoming increasingly frustrated until a letter to the Worcester Evening News put me into contact with a delightful gentleman who had known ‘Hastings’ during the very early days of the company. On seeing the ‘push stick’ picture he quickly identified the person in question as a ‘Geoffrey Prescott’ with an address close to Battenhall Road. |

Here indeed was a conundrum. Prescott or Hastings? Another reader of the Evening News who had actually worked for Ten-Sixty-Six knew him as Mr Hastings so the confusion was deepening. Several months had now passed and I was gathering large amounts of material, which I was not yet able to put into a true context. Through perusal of records at the National Records Office I was reasonably sure who the person was, but it was now vital that I found some proof of the true identity of Hastings/Prescott to make sense of the information I had. Nothing from the records Office in Worcester could give a positive identification for either name, so I decided to pursue another path entirely.

|

In a 1948 issue of Model Car News there was a reference to ‘Hastings’ offering flights in ‘his Auster aircraft’ as prizes at the Whit Monday race meeting at Eaton Bray. Perhaps either ownership of the aircraft or a pilot’s licence would give me the information I sought. The Royal Aero Club that had been responsible for issuing flying licences at the time had been wound up in the 1980s, but it was believed that records had been transferred to the Royal Air Force Museum. A letter to the curator at Hendon produced an immediate response. The ‘Aviator’s Licence’ was still in existence and a further piece of good news was that a photograph was attached to the licence. The licence confirmed my thoughts and identified the person in question as Geoffrey Irving Hastings, living at 26 Battenhall Road Worcester. The photograph showed the same person as featured in the model magazines. I therefore presumed that Hastings was his real name and Prescott the assumed name that could not have been used for the licence. |

|

Geoffrey Hastings was born on 26th April 1907 in Nelson Lancashire. Father Sydney and mother Annie were both weavers in the cotton mills that dominated the towns of Burnley, Nelson and Colne. I have been unable to find any other information regarding Hastings prior to 1939 when he appeared on the electoral role in Worcester for the first time, using the name Geoffrey Prescott. It has not been possible so far to find out exactly what had led Hastings to assume the name of Geoffrey Prescott and it was under this name that he is recorded living until 1951 in St Dunstans Crescent Worcester. Quite how he managed to continue with this dual identity is difficult to understand but he seemed to have a successful existence as Geoffrey Prescott in his private life and as G.I. Hastings in his commercial ventures.

Hastings rented 80 St Dunstans Crescent from a prominent Worcester based builder, William Bennett, and it was here that he first came into contact with the person who was to be the key to his whole future. William Bennett had been very successful, both as a builder and a property speculator and by the end of the 1930s owned a considerable number of properties in Worcester including a row of 7 imposing terraced town houses that his company had built in Battenhall Road. William used one, number 26, as his family home where he lived with his wife Clara and Daughter Gertrude. Gertrude Bennett was born in 1897 and was more commonly known by her second name, Millicent, and although living at home, was an independent lady with her own business interests.

St Dunstans Crescent led directly off Battenhall Road and curved behind the row of properties that included number 26. The very large area that separated 80 St Dunstans Crescent and the Battenhall Road properties included tennis courts, a coach house, garages and other buildings that William used for his business. Millicent and Hastings met ‘over the garden wall’ so to speak and we presume that a relationship quickly developed between them.

William and Clara Bennett died within a few months of each other during 1941 leaving Millicent, still single, and exceedingly wealthy, living alone in a very large house. It seems that Hastings also remained in Worcester throughout the war years, which would indicate that he might well, have been in a reserved occupation or even something more clandestine. Certainly their relationship flourished, and the fact that her business interests included a factory in Cinderford occupied by W.E. Salter Die Casting Ltd may well have encouraged this. These were to be vital elements in the eventual formation of Ten-Sixty-Six.

|

|

The other significant factor in the formation of the company would seem to be the friendship that existed between Hastings and Edgar T Westbury. Edgar Westbury was a legendary figure in the world of model and experimental engineering for nearly four decades. There are references in Model Engineer to Westbury’s ‘friendship’ with Hastings and in one of his articles a photograph shows a young lady ‘winding miniature ignition coils’. The photo was ‘by courtesy Messrs G.J. Hastings’ making the clear inference that this taken in the ‘1066 factory premises’. There are further references to Hastings being the supplier of parts for some of the Westbury constructional projects, possibly via Hastings’ connection with the NIFE battery company. There is no doubt that although Westbury was primarily interested in model hydroplanes he was very involved in the designing of engines, cars and components for the growing hobby of tether car racing. |

All the elements were now in place for the setting up of the company, the die casting company at Cinderford, the availability of an operating base at Battenhall Road, the money provided by Millicent Bennett and the design expertise of Edgar Westbury, all under the stewardship of Geoffrey Irving Hastings.

Ten-Sixty-Six Products Ltd was formed very shortly after the end of the war and registered in late 1945 with an address at 26 Battenhall Road Worcester. The house had been converted into flats after the death of Mr and Mrs Bennett, and Millicent Bennett occupied one, a William and Lillian Glass another, with the remaining space used as offices for the building company, which Millicent had inherited. Hastings’ new company was to share this office space and facilities. There would appear to be some confusion over the actual location of the Company as two early adverts give the address as 26 Battenhall Road, another, 22 Battenhall Road and within weeks an address at Elmers End in Beckenham Kent was used, although ‘a phone number was not yet available’. Equally quickly a move was made to the address at 90 Pimlico Road, London. Pimlico Road remained the advertised address until the end of 1947 when Company ‘apparently’ moved back Worcester, but with a registered office in Birmingham. No evidence has come to light regarding these differing addresses but it seems that the company continued to operate from 26 Battenhall Road for its entire existence. Certainly, a workshop was established in one of the outbuildings at the rear of the terrace.

Initially the staff comprised Mr Hastings as the Managing Director, a Squadron Leader Crowe, whose exact position is unclear but may have been a business partner, the company secretary Pat Brittlebank, a Mrs Levi who managed the finances and accounts and a gentleman who occupied the workshop, but was seldom seen. It has not yet been possible to put a name to this person although it seems he was responsible for some of the fettling work and preparation of materials. Certainly the raw castings were dealt with there, having been delivered from the Cinderford factory. In 1947 Gywnfa Davies and another girl called Jean joined the company from Worcester Secretarial College as shorthand typists. It was, by all accounts a very genteel workplace most unlike a normal company office. Morning coffee and afternoon tea were served by a maid and during winter, when the coal fires in the office needed making up, the maid was summoned by bell when she would fetch the scuttle and attend to the fire.

The first product from Ten-Sixty-Six was to be the Falcon series of model engines. There is little doubt that these were Westbury designs as they shared so many features common to his other engines as well as the ‘Falcon’ name that would seem to follow on logically from his previous design the 5cc ‘Kestrel’. The Falcon engines were designed in the Westbury tradition to be suitable for home construction and were offered either as completed engines or as neatly packaged kits of castings, parts and hardware. Each kit was supplied with a workshop drawing that had originally been produced by John Bishop, a young engineer working for Archdales, who were a leading British machine tool company operating in Worcester. Payment for this drawing was to be a Falcon engine, which for reasons, which will become apparent, did not materialise.

|

|

Through his activities during the war years Hastings seems to have built a large network of connections and acquaintances in the trade who supplied materials, parts, accessories and items of hardware to him. These would be delivered to Battenhall Road, packaged as appropriate with the pressings and castings coming from Cinderford, and then despatched to recognised dealers such as John Bagnall in Stafford, Bonds O Euston Road, and Bud Morgan in Cardiff.

|

From the very first advert in February 1946 that featured the Falcon, it was made clear with the statement "WE DO NOT SUPPLY DIRECT" that the company would only supply retailers. This situation continued unchanged until March 1948 when they indicated that they were prepared to supply directly to customers. Catalogues were however available originally for 7d post free, later rising to a whole shilling (5p). In August of 1946 the company

attended the Model Engineering Exhibition for the first time, displaying the

Falcon I 5cc and Falcon 2 10cc engines. The first items for what would become

the MRC car kit were also on show and these included clutches, wheels and the

Hastings Racing Cord tyres. An on the spot piston and liner honing service was

also offered which was a unique opportunity for visitors. Adverts for parts for

the first model car soon appeared in the specialist magazines and further items

were added throughout the summer and by October 1947 the basic MRC chassis kit was on

offer. |

|

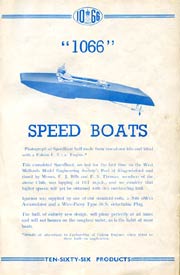

In addition, the show preview mentions a kit of parts for speedboats, but it was not until the following May that the kit for a 24" tethered hydroplane was finally made available. The ‘Westbury’ design influence was again obvious with this kit, which contained the materials to produce a single step ‘Golly’ type boat, similar to the design he published in ME in 1939 and suitable for the Falcon or other 5cc engines. The engine mount and other hardware necessary to complete the hull did not arrive until October. The complete kit was priced at 25 shillings with a 36" version at 45 shillings. A ready to use set of fittings was also available for a further 71 shillings and six pence. |

|

The Company stand at the 1947 Model Engineering Exhibition featured the MRC car chassis, the hydroplane, 5cc and 10cc Falcons and accessories. Another item to be featured was a new 1cc compression ignition (diesel) engine, but no evidence of its existence had come to light until Adrian Duncan found what he believes to be one of these engines. Also on offer were wheels and other parts for OO gauge railways and whilst these were not in the 1066 product range they may well have been produced by, or for, the model supplier R.M. Evans who had moved into 92 Pimlico Road the previous autumn. On the return of 1066 to Worcester, Evans took over 90 Pimlico Road as well, acting as agents for 1066 Products

|

|

|

|

The Evans brochure (above) makes the following statement about the hydroplane. 'This completed speedboat, on test for the first time on the West Midlands Model Engineering Society's pool at Kingswinford and timed by Messrs F J Bills and P S Thomas, members of the above club, was lapping at 19.7mph, and we consider that higher speeds will yet be obtained with this outstanding hull.'

|

|

It was obvious from the advertising copy, however, that things were not running at all smoothly at Ten-Sixty-Six. Early adverts imply that all the items on offer were available, yet soon the tone was to change. The 5cc Falcon was now "almost ready". The 10cc Falcon was "coming soon", kits and ignition components were "available in limited quantities" and dealers would "soon have all chassis parts for the MRC". Clearly, setting out to design, develop and market 3 engines, the components parts for a car and a hydroplane, all within a matter of months, was unrealistic. The net result was that the orders received from dealers and retailers were not being met, as stock was just not available. The difficulties associated with putting this range of products onto the market in such a short space of time was further compounded by the industrial climate of the day, which gave priority to products intended for export. Raw materials and labour were in short supply and most other businesses in the model world were experiencing similar problems. |

By late 47 the situation was so bad that there was nothing at all to send out to the dealers. The list of orders grew and the typists were constantly engaged in sending letters of apology for orders that had not been met. In the letters, Hastings assured all his customers that the situation was now in hand and in a somewhat unwarranted slight added "Now that he had a competent staff they could have full confidence in the company". One of the typists showed John Bishop a sheaf of letters and cheques going back several weeks for goods that did not seem to exist. The situation was also causing a degree of embarrassment elsewhere as parts supplied by the company were being specified in constructional articles in modelling magazines including those by Westbury himself, who had to make an apology of behalf of Ten-Sixty-Six. With no other work on hand, the typists were even reduced to sorting nuts, bolts and other hardware and making up the packs for inclusion in the kits. With so few orders being filled, cash flow would have been a major problem and it was probably Millicent Bennett’s money that was keeping the company afloat. With virtually no income and at least 7 salaries being paid directly this would seem to be the only way that the company survived through this period.

|

In the early summer of 1947 Millicent provided the money for a company aeroplane. Given the financial state and size of the company there is no way could it be justified on a business basis, but Auster Aircraft of Rearsby supplied a new JI Autocrat G-AIJW to Ten-Sixty-Six Products and this was registered to the company in June of 47. Whilst Hastings was not able to fly at this stage, one assumes that, being a Squadron Leader, Crowe could, but he was soon to leave the company. Hastings started flying lessons at the Hereford Aero Club and finally gained his Aviators Certificate #24755 on the 21st of July 1948 in the Auster. Jean, the typist, recalled seeing pictures of the aircraft on the office wall and as part of her duties she had to record the Ministry of Aviation airfield updates every month for Hastings. At her interview Hastings asked if she had ever flown before and then to her great surprise promised her flights to various trade fairs as a perk of the job. Another promise he was not to keep. |

|

|

Auster being inspected by staff at Eaton Bray on 10 March 1948 having been flown in by Sqn Ldr Crow. |

In April of 1948, the Company advertised that they would be exhibiting at The British Industry Fair. On offer was a pressed aluminium body for the car as well as a completely machined MRC kit that was to be "available from the 10th April". It seemed by this stage that Hastings had managed to resolve most of the supply issues and stock was beginning to get out to the dealers. This had largely been accomplished by installing production machinery and equipment at the Cinderford works to manufacture many of the items listed. It was quite obvious though, that other companies were also undertaking production and machining work, as Cinderford did not have the facilities to accommodate all of the diverse range of products. There is evidence to suggest that production was ‘piggy backed’ onto other contracts, as the level of sales could not support the sheer quantity of items being manufactured.

|

This is further reinforced by the introduction of a new engine, the Hawk. Still sharing most of the Westbury features, as well as continuing with the ‘birds of prey’ names, this engine was only offered as a completely finished unit and, even then, only for export. Although the Falcon was offered as a complete ready to run engine there is no evidence that any factory made engines exist, so the Hawk is the first engines that could be confirmed as a ‘production engine’. Later in the year came a noticeable change of emphasis when a completely new car and new engine were introduced. The Westbury connection using ‘birds of prey’ names was dropped and, in a cunning piece of marketing, the Battle of Hastings theme was extended to make a more obvious connection between his own name, that of the company and the products. The new 10cc-racing engine was to be the ‘Conqueror’ and the new racing car the ‘Conquest’. In addition a new logo was registered to make the transformation complete. Development of the Conqueror engine continued through a number of marks and specifications and in April 1949 yet another new engine was introduced. This was a 5cc-racing engine, which continued with the 1066 theme being called the ‘Arrow’. With Hastings, Ten Sixty-Six, Conqueror, Conquest and Arrow it is intriguing to consider what the next car or engine might have been called had the company survived? |

|

|

|

Throughout the life of the company Hastings was a great publicist for Ten-Sixty- Six as well as being a very generous patron and sponsor of tether car racing. During the spring of 1948 he had a private 70ft track built at Ambrose Farm in the St John’s suburb of Worcester, in order to ‘help to develop the Company’s products’. The track was opened on 27th June and was made available for competitions, hosting the national finals in 1950 even though the company had effectively ceased trading by this time. The track continued to operate and in 1952 was passed over to a new club formed by the amalgamation of the existing Birmingham and Worcester clubs. Mr Hastings was appointed as the Honorary President of the new club. The track was still in existence as late as 1987 when Mr Cartlidge, who owned the land, finally bulldozed it. |

|

To coincide with the opening of the track Hastings also offered a trophy for competition in order to encourage the development of British products and publicise their success. The Hastings Trophy, as it was duly called, was valued at 200 guineas and the competition had a complex series of rules designed to reward home construction. Medals were to be awarded to finalists, and area winners. The first running at Eaton Bray on August 15th featured most of the leading competitors of the time including John Oliver, Gerry Buck, Basil Miles, Jack Morgan, Jack Gascoigne and the Snelling brothers. The event was won by Jack Parker with his ED powered car. Mr Hastings went even further by awarding further cups to John Oliver and Gerry Buck for ‘good efforts with British cars and engines’. A major revision of the rules was put into place for 1949 to further enhance the ‘home built’ aspect of the competition, but the demise of the company seemed to spell the end for the Hastings Trophy as well. |

|

Whether by personal contact or some commercial tie up, the parts supplied by the company provided further extensive advertising by being featured in many of the designs for cars published in the late 40s. Several of Harold Pratley’s plans show extensive use of products sourced from Worcester, which in turn led to many home built cars featuring these items with even more exposure for the company. Lawrence Sparey gave detailed instructions for machining the MRC axle unit in a 1947 issue of Model Engineer.

Hastings regularly donated kits, parts and motors for events at aeromodelling and hydroplane events as well as for the tethered cars, although winning did not always produce the expected results as was discovered by Ray Monks, a member of the GB model aircraft team. He attended a meeting in the Midlands and won an event that offered a Falcon motor as first prize. Mr Hastings duly presented the motor, but this turned out to be somewhat symbolic as he immediately took it back declaring that it was ‘faulty’ and that he needed to rectify the problem. As far as it is known that was the last Ray ever saw of his Falcon.

This ‘faulty’ Falcon is an example of another problem that bedevilled Ten-Sixty-Six throughout its existence that of quality control. In spite of the extravagant claims in adverts and catalogues, the performance and quality of the products was not what it might have been. As well as supply difficulties, the quality of many items was suspect. A near neighbour to the Battenhall Road premises during the late 40s recalls large quantities of castings and other parts being thrown out from the workshop onto waste ground nearby. He estimated recently that enough had been dumped there to make at least 5 wheelbarrow loads although much of this looked quite useable to him. In a conversation, an ex employee remarked that ‘he could not see how the company made a profit as the poor quality of the products being manufactured meant that they usually ended up scrapping more than they were ever able to use’.

|

|

|

|

As recognised companies were producing many of the components, I would imagine this referred primarily to castings and other parts being worked on by 1066 employees. There seemed to be no one immediately connected with the company who had sufficient skills and knowledge to machine parts to the degree of accuracy required. Certainly when the engines were being ‘factory built’ it is almost certain that an existing model engine company was producing these. All factory built engines had a CHM serial number and given the Westbury connection I consider that Craftsmanship Models in Ipswich to be the most likely source of these motors.

By 1949 the modelling scene was undergoing a significant change. Cars, engines and boats were becoming more sophisticated (and faster). The pioneering, home building spirit of the early post war period had largely been replaced by a far more competitive attitude. American imports were becoming more common and development in the States had left British products sorely lagging in performance. After a long court case, purchase tax was being levied on parts and components as well as the finished items putting companies under further pressure. Ten-Sixty-Six however, was still busy churning out kits, parts and engines for a market that was rapidly declining.

In the December 1949 issue of Model Car News, the Editor gives the impression of a company that was flourishing, commenting on the ‘pleasure of a recent visit to Messrs Ten-Sixty-Six Products of 26 Battenhall Road Worcester and of inspecting ad lib a quantity of components’. The article went on to remark on ‘the many interesting, hitherto unpublished articles (products) in the course of development in their experimental department’. He took the opportunity to announce cuts in price of the MRC kits of around 1/3rd and adds an interesting comment that ‘everything he saw was of the very highest quality’ Thus the impression is given of a substantial factory rather than a shed in the garden of a private house, which would indicate that he had travelled to the Cinderford works. Although there are several references to the ‘factory premises’ and ‘our own works’ its location was never publicised. No evidence of any of these 'interesting products' ever emerged until just recently although there was a clue in an engine that appeared in Clanford's book, which featured a Conqueror with a down draught venturi.

|

By the time this article appeared however the real situation was somewhat different. The company was soon to disappear from public view. The very last advert in Model Car News appeared in January 1950 and featured the slightly quirky ‘two at a time’ model car racing system with a review on the Conquest car in the same issue. Adverts for the Conqueror castings sets continued in Model Engineer until July but there is no further mention of Ten-Sixty-Six after that, so what did become of Mr Hastings and the Company? Taking into account the very extravagant way the company was operated, and the level of sales of its products, it is questionable whether Ten-Sixty-Six could ever have made a realistic profit and more than likely that it was recording significant losses throughout its whole existence. Judging by the amount of waste recorded and the huge quantity of new parts that remained unsold, production must have grossly exceeded sales over the life of the company. Right: Last ever adverts Jan 1950 MCN and July 1950 ME |

|

|

The introduction of two new engines, a new car and then further marks of the Conqueror all within twelve months would have added further to the already parlous financial situation. The cost of the design and development of these new products with the attendant cost of new dies, components, hardware, packaging, advertising and marketing was a huge investment which the level of sales would have been unable to support.

It seems fairly obvious that the company was not financially sustainable, and could never have been viable on its modelling activities alone. Millicent Bennett had been keeping the company afloat. She had invested many thousands of pounds in Ten-Sixty-Six over the years to keep it operating, with no obvious return and there was now very little market for what the company was producing either. Whether it was because of these financial considerations, loss of interest or something more sinister is not known, but by early 1950 the whole situation with regard to Hasting’ personal life and Ten-Sixty-Six had changed dramatically. Hastings abandoned Ten-Sixty-Six Products as a trading name and became ‘G.I. Hastings. Manufacturer and Exporter’.

|

|

The complete range of products previously available was still on offer from 26 Battenhall Road with the same phone number. His letterhead shows him to be ‘manufacturer and exporter of 1066 products’. The Auster was however sold to a French company, re registered and operated in Africa where it was destroyed in 1954. The factory at Steam Mills, Cinderford continued in operation and may even have continued to produce castings if and when there was any demand. |

Hastings and Millicent split their time between Worcester and Falmouth where they lived as man and wife in a mobile home under the name of Prescott. Millicent still owned numerous properties and continued with her building and property development interests. It was not long before they were involved in yet another business venture. Millicent bought a fishing boat called Talisman, which was based at Looe in Cornwall, and from here they used to run shark fishing trips.

|

More interesting facts about Hastings’ business methods come to light during this period. In 1952 the die casting company was running into difficulties and they decided to issue 1000 £1 shares. Hastings who was already a director bought 780 shares. Millicent also put nearly £3000 into the company. Another issue, this time of 5000 shares and a further loan from Millicent of £7000+ was not enough to keep it solvent and late in 53 W.E. Salter Die Castings Ltd went in to voluntary liquidation. It transpired however that Hastings had used his position as director to purchase quantities of goods, including a car, fishing tackle and supposedly another Hastings trophy, this time for the Bristol Motorcycle and Light Car Club and charged it all to Salters. This came to light when the company was wound up and led to Hastings being pursued for the money. It also caused embarrassment when the liquidator wanted the trophy back or £280 to cover the cost. One supplier comments, "we have a very poor opinion of Mr Hastings’ business methods". |

|

Geoffrey Hasting and Millicent continued to live in Falmouth and run the fishing trips until 1957 when a car journey ended in disaster. On the 12th of September they were travelling to Looe from Falmouth and for some reason Hastings was driving instead of Millicent, which was more usual. On a long downhill stretch of road Hastings pulled out to pass another vehicle and was involved in a head on collision. Millicent survived with serious head and facial injuries but Geoffrey Hastings died instantly. He was just 50 when he was killed.

After her recovery, Miss Bennett, who was now sixty, moved to a bungalow that had been built for her at Powick just outside Worcester where she lived until she died aged 89 in 1986. The vacated space at 26 Battenhall Road was let as another flat and what remained of Ten-Sixty-Six Products and G.I. Hastings Manufacturers and Exporters was moved to Millicent’s bungalow where it remained for many years.

|

|

26 Battenhall Road still exists and has now been subdivided into 6 flats. The tennis courts have given way to a row of bungalows and the garden and yards to the rear of 26 have become garaging and car parking. The rest of the area is now allotments and the remains of what was the Ten-Sixty-Six workshop is still under the surface of these. It is quite likely that much of the scrap is still buried there as well. A local resident believed that at some stage Geoffrey might have had a son, which was indeed true and identified as the source of the ‘hoard of parts’ in Kent. The son has since died, but I have been in contact with the grandson of Hastings/Prescott who was unaware of the unusual background of his grandfather.

|

|

90 Pimlico Road passed initially from R.M. Evans to a famous interior designer Geoffrey Bennison in the early 60s. The factory at Cinderford now houses small business units including a maker of traditional wooden toys. Amazingly, the items removed to Millicent’s bungalow remained there long after she died having passed, along with the property, to her niece. Unfortunately much of it, including the film that the company had produced, showing the Conqueror motor being developed and raced, was thrown out during a clearing out session. However an invite to investigate the niece’s garage did produce most of the records of the company, including all the insolvency material and numerous other documents, all of which were donated to OTW and formed much of the basis for the details in this article |

The retailers who still had stocks of the products continued to offer these for sale. John Bagnall was advertising items for a further ten years, but even hefty discounting could not clear these stocks and finally he disposed of what remained to Gerry Buck. With the current renewed interest in tethered cars, much of the material that had remained unsold or unused has now reappeared on the market. Complete kits for engines, and cars, large quantities of individual items and spare parts have emerged recently. Which is where I began.

So ended my quest to record something of the history and activities of Mr Hastings and Ten Sixty Six. There are still gaps, but given the background of the gentleman concerned this is hardly surprising. Those who knew him have described him in less than complimentary terms. One ex employee describes him as ‘ebullient, almost to the point of being a show off’.

I am indebted to all those people in the tether car fraternity and others who provided me with material, information and reminiscences. My particular thanks go to John Bishop, Susan Campbell, Jean Davies, Iris Davies and Vic Smith. Without their help the article would have been very short and probably libellous. Thanks also to the late Richard Riding, Peter and Wendy Thomas and the Westbury family for images

©copyrightOTW2021