|

Home Updates Hydros Cars Engines Contacts Links Racing Contact On The Wire |

Work Bench: A ‘Killer’ in our midst

What began as a casual ‘would you like a winter project’ conversation started a trip back into tethered car history and an exploration of the remarkable thinking and developments that went on in the 1.5cc and 2.5cc classes during the 1950s. The story begins with the Olivers, father and son and the introduction of the Tiger MkII twinshaft in 1951. So successful was this motor that it became the engine of choice for all, either in Oliver supplied cars or home built models. Like now, the universal adoption of an already top-notch engine introduces the constant dilemma of 'how can I make mine go faster than theirs'? Witches brew fuel, engine tuning, optimising settings, but then where?

The Catchpoles were early in the lateral thinking department with the 'Bottoms Up', using two chassis pans, one on top of the other, to cut down frontal area. The Snelling brothers tried streamlining by putting spats over the wheels and running the car blunt end first. Many others, including Ron Thrower, and Roland Salomon went the Bottoms Up route, but with their own castings, pressings and composite chassis. Both Ron and Roland became record holders with their two cars, Ron’s 1.5cc GRP car and Roland’s 2.5cc SuperSabre with pressed aluminium halves.

|

|

| Ron Thrower's GRP car | Roland Salomon's SuperSabre |

However, as the motors were developed further, the revs went up and tyres got smaller, even down to two inches in diameter. Eventually there was hardly any ground clearance, which led on to the next and fairly drastic step. The Oliver has a ¼ inch flange on the bottom of the crankcase for mounting to a pan. This also gives the characteristic upward tilt to the cylinder axis. Machine off this flange parallel with the cylinder axis and voila, ¼ inch extra ground clearance and lower top line to the body as well. Now, how do you hold the motor into the car? Answer, machine the top and bottom castings of the car so accurately that the motor is sandwiched between the two when it is screwed together, and numerous versions of this very radical solution appeared, including examples from Jim Dean, Arne Zetterstrom in Sweden and the 'Stiletto' from Roland Salomon in Switzerland. In Roland and Jim’s case, the only screws used were to hold the two halves of the body together, which kept the motor, front axle, tank and cut-off all in place when the car was put together. The motors were also radically lightened.

|

|

| Stiletto | Jim Dean's Incendiary |

Roland is now central to the continuation of this project. Although the 'Stiletto' was very successful, he considered that the 'Sabre' was faster, but even the most ardent Oliver twinshaft enthusiasts had reached the conclusion that tyres were now unrealistically small and that some form of gearing was required to allow a larger and more reliable range of conventional wheels and tyres to be used.

|

Putting spur gears on each end of an Oliver was tried by Jim Dean amongst others, first with 'Incendiary' and then a more conventional 'Bottoms Up', but was hugely complicated, requiring very precise engineering. This in turn led to a single ended Tiger aero motor being used on a spur gear mount. Ken Procter described his version, and like Ian Moore with his bevel drive 'Shadow', the first thing that happens is that the mounting lugs are cut off, requiring a custom made mount that clamps on to the bearing housing, supports the back of the motor and the cylinder head. The Olivers did finally come up with a purpose built motor that overcame this problem, but that never made it into production. |

|

Although he did have one of Ken Procter’s 'Supercortemaggiore' pans that he had run with an ED engine and which later served as a test bed for the twinshaft for 'SuperSabre', Roland decided on a different approach for the new car. The first step was to build a prototype of what would become ‘The Killer’, his most successful car and a regular winner, both for him and for those that built replicas.

|

The new car was based on a cast pan that was very short but wide enough to accommodate the transverse motor. The pan was cut off square at the front and rear and just 5/8ths deep. To test the principle the much modified twinshaft was pressed into use, but how it was mounted is something of a mystery. With just the motor, tank and cut out fitted, trial runs allowed Roland to work out the details of the final design, using bar stock materials rather than castings that Ken Procter had used. Two parallel mounts sit on pads in the pan with a tubular bearing carrier between them clamped by the rear holding down bolts. The bearing housing of the motor is clamped in one mount, with the back of the motor bolted to the rear mount. A head steady takes care of torque from the motor. 1.5:1 gearing allowed rear tyres of 80mm to be run. A very thin body shell covered the pan, extending well beyond the front and rear creating a very streamlined shape with plenty of ground clearance Right: Roland Salomon on right with Ken Procter and 1958 European Championship medal. |

|

The success of this car cannot be understated setting World and European records and winning three European and two World Championships in the process before Roland retired from tethered car racing at the end of the 1950s to take up Kart and Formula 2 car racing. His earlier cars were described in Model Maker in 1957 and the plans for 'Killer' published in 1958, a footnote in tethered car history---until 2013 that is. At the European Championships in Basel, there was Roland Salomon, talking to Werner Metzger whilst looking at a very nice 'Killer' replica. What then transpired was somewhat amazing as it was revealed that the chassis of the prototype was still in existence. Six years later, this was what I was offered as the ‘winter project’. Yes, a lot was missing, but what was there was a piece of tethered car history, so yes please. If that was not coincidence enough, amongst the material that arrived from one of our correspondents a couple of year back was a set of plans for the car. Even more odd, Michael Schmutz posted a photo last year of another set of plans that had been discovered.

|

|

|

| Werner Metzger and Roland Salomon | Original Swiss 1.5cc Killer | |

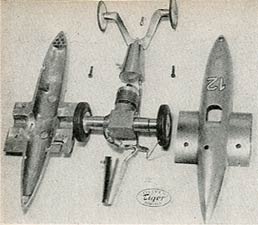

The package that arrived had the pan, with the position of the cut out confirming that no body had ever been fitted, sets of original Hostettler EHZ wheels and tyres both front and rear and a printed article about it in German. It was immediately obvious from the pan, that the engine (whatever it was) had not been mounted using the system that was developed for the single ended motor. The consensus was that the motor used for tests was bolted to some sort of plate, held down by three 4mm screws through the pan.

|

|

| The 'kit of parts' | Pan showing extensive machining and grinding |

|

There was no way that a single ended motor could be used as there were no pads for the mounts and the machined bottom portion was too narrow for anything other than the twinshaft. The sides of the pan were also machined out for large bearing housings rather than an 8mm axle, something of a dilemma? With the original motor long gone and no chance of a replacement and genuine Olivers non existent, I was stymied until I recalled that at Old Warden a while ago John Goodall had shown me a couple of twinshaft crankcases and assorted bits. At the Retro Meeting last October I asked John if there was any possibility of putting together a complete unit for me as I wanted to keep the car as original as possible. I did baulk at machining off the mounting foot of a perfectly good engine though. After a deal of consideration, John agreed and set to work on a lovely MkII twinshaft, which arrived, fully tested, in January. |

|

In the mean while, a simple sprung steel front axle with teardrop ends was cut out and silver soldered together and the cut out spindle lengthened so a body could be fitted for display purposes. A trial assembly with a borrowed motor confirmed that, with a bit of judicious work, an intact twinshaft would fit. As it was my intention to make a body to finish the car off, the overall height would not have to be increased.

|

|

The body was carved out during the Christmas break, and sad to say, the inside was milled out before shaping the outside. It all fitted well, the only question was whether it would still fit when the new motor was installed? John worked on the motor over Christmas as well and after running in and testing on a prop it was down to me to fit it. Having no clue as to how the original was installed and not being willing to machine off the mounting flange I did resort to drilling four holes in the pan. Getting those in the correct position is always an adventure with an Oliver style twinshaft but everything lined up OK. Just a matter of fitting the EHZ wheels instead of Raylites and another bit of luck, the tube nuts and inner washers fitted the wheels perfectly giving the correct width between wheel centres. The body needed relieving slightly to accommodate the slope of the cylinder and drilling for the needle valve and securing screw. Four coats of cardinal red paint, appropriate decoration and it was done. I did have some repro Oliver waterslide decals, but these only work on a white background, as I found to my cost.

|

|

So there it is, the prototype ‘Killer’ resurrected, and now with a body that it never possessed in its original incarnation. At least, not ever having had a body, I am unlikely to have the surreal experience of having had a GRP body made for a car I had rebuilt, only to have someone else give me the original the same day as the new one was delivered?

I am most grateful to the following for the realisation of this project and the information connected to it. Philipp Meier, Werner Metzger, Roland Salomon, John Goodall, Jim Hampton and Eric Offen.

Buying a tethered car by accident

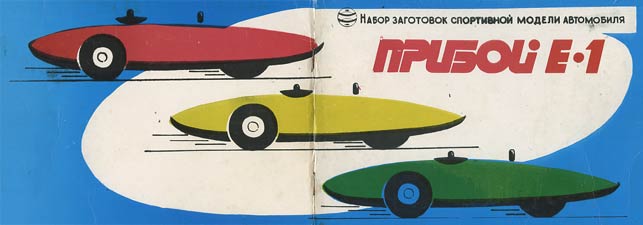

Scanning the ebay listings in the vain hope that there might be something to pique the interest I came across a Russian E2 tethered car kit, the one with a box full of raw materials a cast pan and a long detailed set of building notes in Cyrillic. Unusually, the item was in England but as I already had one it was not immediately worthy of consideration, but after zooming in on the photos, a commercial gearbox case could be seen, which was a much more attractive proposition. At this stage the location and name on the listing did not ring any bells and the finishing price was well beyond what I considered realistic adding it to the ever growing list of ‘those that got away’.

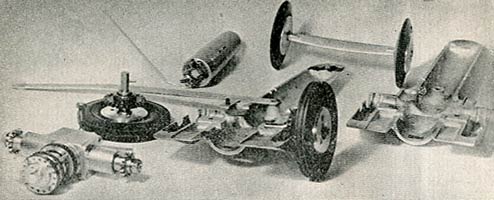

Fast forward a couple of years to a Retro Club track day and another of those coincidences that continue to defy logic, for there was the self same E2 kit in its original polystyrene box, However, it was now in a cardboard box that had been used to despatch it to the winning bidder, a fellow member of the Retro Club, which bore more details that allowed the recent history of this item to be put together. Following his visits to Orebro in the early 2000s where he ran his original cars and engines, John Oliver had obtained this kit from a Swedish racer. After his death in 2016, this was one of the items that was sold by his family via ebay. A delve in the box revealed the same gearbox case, plus a bag of other parts, but strangely, they were all factory finished and anodised and ready to run. The owner reckoned that he had paid over the odds and was unlikely to build the E2 so it was all for sale and knowing now that the gearbox was complete, a deal was struck.

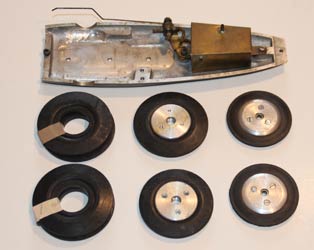

What I had not realised at the time was that as well as the raw E2 kit in its packing and the gearbox, the cardboard box also contained a complete E1 1.5cc car, yes, complete and factory made. All the parts, including the gearbox, finished and anodised, and a machined pan along with all brackets, bearings, wheels, suspension and fixings as well as a fuel cut-off. Even the still sealed instruction book and drawings were for the E1 not the 2.5cc car. All that was missing was a fuel tank and the lever for the fuel cut-off, even the tailskid with the brazed on piece of tungsten carbide was there.

As a construction project, this must have been the quickest ever as the entire work schedule could be summed up as, drill and tap fourteen holes, assemble gearbox, make an arm for the fuel cut-off and a tank and then bolt it all into the chassis. The new lever for the knock off cost me another piece of carbon steel ruler, which is ideal for these and sprung front axles, but requires ferreting out at exhibitions and swap meets as they are now in short supply. The pan is very slim at the front so there is not a lot of room for a tank, so that had to be fitted round the knock off.

|

|

|

| Gearbox and trunnions, wheels, collars and rear suspension | Motor with coupling | Knock off |

|

|

| Tank with cut out to accommodate fuel knock off | Front wheels, carrier and suspension |

|

|

It is a peculiarity of many of the Russian cars of the period that they did not use tuned pipes or exhausts of any sort, even though the 1.5cc and 2.5cc motors supplied have the stubs and rubber rings for pipes and come complete with pipes when purchased. This did involve a bit of design work and machining on the rear of the pan to attach a pipe support, but there it was, a complete E1 car with minimal effort and time but with a huge slice of luck and coincidence. Something of a contrast in terms of machining and work required to the similar one that Oliver Monk is building and featuring in his latest series of constructional articles. |

|

The observant will notice that the car is still naked as is another modern car built last year. Blue foam and GRP is the answer, but so far courage and only being able to work outdoors with ‘smelly stuff’ has prevented me making a start. Thanks to the encouragement and advice from Oliver Monk I have resolved to give it a go. I can always revert to wood if it all goes pear shaped, oh I hate bodywork, a dislike shared by another well known enthusiast and prolific builder as I found out recently. With at least three of these cars now in existence in the UK, there is a plan to use them at Buckminster, as and when we are able to return there. |

|

©copyrightOTW2020