|

Home Updates Hydros Cars Engines Contacts Links Racing Next→ Contact On The Wire |

Pitbox Special

A major discovery, but only by accident

There are two stages to identifying any car or boat, what it is, and whose it was, inevitably and significantly the more difficult part, and often an impossible quest. Commercial items are relatively easy to recognise, as there is an untold amount of printed material, home built somewhat more problematic. Establishing a provenance, builder, owner and a race history if there is one is down to detective work and a large degree of luck, and it is a massive dose of the luck element that dominates one of the most important discoveries for a long while.

Like any good detective story there has to be clues and evidence, and with commercial cars it is observable features that would distinguish it from any other of the same make. More importantly, there has to have been printed and photographic records that show these features, along with sufficient captions or text to be able to make a positive attribute. This is where hours of research, allied to a large chunk of luck, can pay dividends, or as more frequently the case, stall entirely through the lack of evidence.

This saga started back in 2020 with an email to OTW, asking if we could help identify a collection of tethered cars, not a problem as all ten were commercial, mostly American and a mixture of originals and reproductions. Nothing more was heard for many months until a host of emails arrived from the same source that showed over a hundred engines as well as the cars. It transpired that this was the collection of the late Jim Lee, a long time member of the Retro Racing Club who had died the previous year, and the emails were from a distant family member who was tasked with disposing of it all. Having offered to catalogue and value the collection, I became all too aware of the huge number of items involved. What no one had initially realised was that, in addition to what had been photographed, there was an equal amount of car and engine spares and accessories, far beyond what anyone could imagine, starting with well over 100 pairs of new tyres alone.

After an estimation of the total value and discussions about possible routes to pursue for disposal, the family decided to offer the entire collection as one lot, and could we suggest people who might be interested in bidding? Having asked around at Buckminster I passed on some names, and eventually it was all taken on by Paul Goodall. It was not until we visited Paul and John in November to see it all laid out that the sheer enormity of the collection could be appreciated, but it was the cars we were particularly interested in, for obvious reasons. Not often that three Dooling Arrows are discovered and whilst one was a complete kit for a Sanderson reproduction, the other two were original Fairabend style cars, but both as selections of parts in boxes. One, a pretty much standard example of an Arrow, although with a Lexan body as well as a GRP original, but the other was a bobtail with several unusual features that just might give a lead as to its origins.

|

|

|

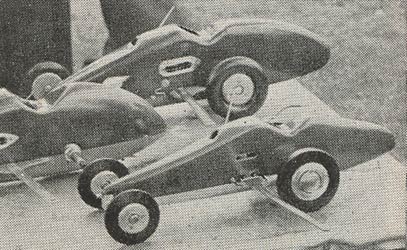

| Standard Dooling Arrow, mostly complete | Bobtail Arrow parts | Sanderson repro Arrow in kit form |

Although Dooling motors and the Arrow car are of American origin, their part in British tethered car history is extremely significant, continuing through to the end of the sport in the late 50s and beyond. The Arrow had a cast aluminium pan with tether brackets front and rear, direct drive through bevel gears, any form of gearbox having been dispensed with. Coil ignition with a pack of pen cells in the rear of the car was standard along with a straight front axle and rubber bush in the middle, all covered with a GRP ‘proto’ style body. The bridle was a conventional, triangular, piano wire type, picking up on the two tether brackets. In this form the Arrow was fast and made an immediate impact, but in the mid west of the US, a racer by the name of Glenn Fairabend started producing parts to modify the standard cars, and these are easily identifiable. There were dropped front axles from stainless steel, streamlined, aircraft strut material, a casting for a pan handle, and the pan handles also of the SS strut material that did away with the existing tether brackets. In addition there were tailskids from the same, streamlined, material. In Britain, the 5cc class was dominated by Dooling engines, as was the 10cc class, and here the Arrow was the most popular car by far, despite the difficulties and costs in obtaining one in the post-war UK. One of our correspondents recalls riding his motorcycle all the way from Tyneside to Maidstone and back to purchase a complete Arrow car from Bill Bennett.

With the importance of the Arrow to the British tether car history and being short of a winter project, a deal was done for the bobtail, but an entirely spur of the moment urge overcame me and the second box of Arrow bits was also acquired. The degree of luck involved in this last minute decision, would not become apparent for a while though. Having brought the dusty boxes home, it was obvious that both cars had been more or less complete at some stage, yet had been taken apart, with everything just thrown into the boxes, including all nuts, screws, spacers, bushes, circlips and more. The first task then was sorting out just what parts were there, what was missing and seeing what fitted where. In short order there were two cars on their wheels, but that is where it started to become a bit interesting. The standard car had nothing that would distinguish it from any other Dooling Arrow, apart from a race number, but the bobtail has several features that were significant. The tank mounts had all been machined away and a very large, home built tank was in the box instead of an original.

|

|

The body clips were from a single piece of wire that went right through the pan and, most importantly, lurking in the bottom of the box was a strangely shaped brass box and lots of lose lead sheets with holes in them. The sheets fitted into the box with one long screw through them all and two holes in the back of the car exactly matched the holes in the bracket on the box. I presumed that this was to counteract the removal of the tail of the pan and batteries, indicating that the engine probably had a magneto, although the original Dooling that came with the car was an ex speed motor with a trimmed exhaust. Here was another odd coincidence though, as this motor was trimmed identically to the one Ian Moore used in his number 12 car? Left: brass box and lead sheets |

|

All of this was of no use whatsoever as none of our source material had anything remotely like the car, although a photo on the front of a Model Maker in 1956 did show a bobtail Arrow with two identical holes in the back of the pan. The photo was in reference to an article by Jim Dean, who was running a bobtail car that year, but the tank, and wheels were very different, so no further forward. It was whilst preparing an unrelated article for the March edition of OTW that one of those uncanny coincidences, or strokes of luck, occurred and these continue to amaze us. Trawling through the fantastic photo archives on the Swiss Model Car Club site for images of the Zurich track, there was the car with the brass and lead weight box very evident, and holding it, none other than Jim Dean, one of the most successful British racers of the 50s. With this one piece of evidence, many other bits of previously unconnected research fell into place. More captioned images and details soon emerged, photos of Jim with the car, race reports, and of course, his article in Model Maker, ‘Scuderia Dean for 56’ tied everything together. |

|

|

|

Jim Dean came from Slough in Buckinghamshire and was one of a very select group of British competitors that raced both in national and international events. He was also a very busy racer as he would run cars in every class, and extremely innovative as well, his cars all showing individual design elements that make his cars distinctive, if close up images of them can be found. By an equally strange coincidence, two of his 2.5cc cars were pictured in the USA in 2021, but the long time owner had no idea that they were even British, let alone whose they were, being under the impression that his father had built them. Within a couple of weeks, I had a pretty good idea of the history and race record of the car, which was impressive. Although there is mention of Jim racing a ‘modified Dooling Arrow’ in 1952, where he was second in Monza, the earliest an Arrow of his that can be positively placed is at Zurich in 1953, where he won his first European Championship at a speed of 191.04kph (118mph), but as it transpires with the original 1952 car, not the one discovered as first thought. Jim won a second European Championship at Woodside in 1954, this time with the newer car. |

|

Trips to Zurich and the occasional double header to include Monza were the norm for a number of British competitors in the 1950s, such as June 1954 where Jim finished second to Ian Moore at both venues. Ian set a new European record at Zurich during the meeting, raced at Monza and then sold his car to Philip Rochat before retiring from the sport. Nothing has been gleaned from the intervening years, which brings me to 1956, the article, photos from Zurich where Jim won the 10cc class again and the postponed National Championships at Blackpool when he became the British 10cc Champion. Several photos exist of Jim with his cars, but apart from the image from Zurich, all far too small and indistinct to be of any help and in the earlier one on the right he has his hand inconveniently placed over the rear of the car so no indication of whether it had a weight box. What is not widely appreciated is that Jim had lost one arm so had to do all his engineering, car preparation and running with just his left hand, not immediately obvious in most photos, unless you are aware of this difficulty. There was no British team at the 56 Championships at Vasteras and no record of Jim in 57 at Dortmund. Right: Jim's cars at Landikon 1953, including 2.5cc 'Incendiary' |

|

There is a photo of two of Jim's 10cc cars at Mote Park in 1957, one is the bobtail, the other as yet unidentified, but clearly not one of his Arrows, and missing its rear wheels that had been loaned to Ken Bedford for his ETA car seen here at the front.

|

|

| Jim, extreme right, National Champion Blackpool 1956 | Mote Park 1957. Car at rear |

The final mention of Jim and his cars is the double header World and European Championships at Zurich and Basel in 1958, but according to reports, Jim was unable to attend so that his cars were being proxy run by Jack Cook. In a photo of Jack and Les Williamson from Basel, Jim’s car with its racing number 1 is on Jack’s pit bench. Ironically, both Jim’s cars beat Jack by a considerable margin at both events.

That was effectively the end of tethered car racing in the UK and no further mention of Jim or his cars until 1975 and an exchange of letters between him and an avid British collector indicating that some of his cars were for sale. The price being asked was apparently far too high as in Jim's words he 'was going to sell them to the Americans as they would pay much more', but sadly Jim Dean died very soon after. The story does not end there though as a number of contacts report seeing the cars for sale at the London Model Engineer Exhibition around 1977/8. Whether a friend or relative of Jim’s were selling these, or they were on the stall of a somewhat infamous dealer cannot be ascertained, but this does tie in with the death of Jim’s wife in 1977. One must assume that some of the cars were complete at the time, but how then did Jim Dean’s bobtail Dooling Arrow end up, disassembled, in Hackney, in the possession of Jim Lee?

|

This we will never know know, but the Dooling 61 with a magneto might well have proved too tempting a sale prospect as was common at that time when the engines were more valuable than the cars. Suffice to say though that the car was more or less back together after many years. This though is where the luck element in purchasing the second box came in, as the images that I had found showed that parts from the cars had been mixed up in the two boxes, including the entire rear axle assemblies and wheels. Whilst all items were from the same manufacturer and did fit, after a fashion, they did not belong to the car they were being sold with. John Goodall had remarked that the Dooling engine did not seem to fit the bobtail chassis properly, and this was the reason, Change the axles over and suddenly, everything fitted and ran freely in both cars. Right: Bits from the box assembled |

|

|

Now that I had a number of references and photographs of the car, as well as the description from Model Maker a serious degree of confusion crept in. Dean stated in 1956 that he had two cars, one conventional and one bobtail, but in photos both cars variously appear with C&R or Dooling rear wheels. One car can also be seen with a version of the leading link front suspension that Jim used on his smaller cars, but again, not regularly, even in the same year. Lastly, the tank changes between one with a cutaway for the Dooling venturi and the even larger one without the cutaway that was with the car, and as photos show, also in the standard car at one stage. Even the venting system changed on the tanks between photos. Both these tanks fill the front area of the car, which is why the original mounts have been drilled away and both tanks have very solid stainless steel mounts front and rear, the front mounts picking up somehow on the front suspension plate. Left: Jim watches as Paul Zere connects his car to the cable, while Alec Snelling waits to push it off on its winning run at the Woodside European Championships in 1954. |

My suspicion was that parts were mixed and matched regularly between the two cars, which has now been confirmed by another set of photographs from Lyndon Bedford. These show that the suspension was swapped between the bobtail and standard car, as were the wheels and tyres and that the larger tank with the twin front brackets was used in conjunction with the sprung front suspension, but not exclusively.

|

A tale then of a purchase that, thanks to a serious dose of luck and coincidence, has most unexpectedly turned out to be the most rare of finds, a British car that has a European Championship to its name. Only five British competitors, Jack Cook, Stan Drayson, Ken Procter, Jim Dean and David Giles have ever won European Championships, and apart from David Giles’ 5cc car from 1979, Jim’s is now the only other known to exist (until 2025). There is a postscript though as more information became available via John Lorenz. A description of the car and a photo enabled him to identify it as having been built by Joe Ilg, a racer from Laureldale in Pennsylvania. Joe was well known for his modified and hand built 5cc and 10cc cars, with photos of his own cars confirming that certain features on the Dean car were unique to Ilg built cars. This raised the question as to how it came to be in the UK, and here we delve into the realms of speculation. Right: Jim pushing off, one handed at Landikon |

|

Jim Dean, amongst others, raced Borden (mite) cars in the 5cc class, with one of his close rivals being Joe Shelton, an American service man. It is known that Joe Ilg was a supplier of Borden cars and that Shelton did get his Borden from Ilg and there is a distinct probability that all the Bordens being run in the UK at that time had come via the two Joes. Joe also raced regularly with Glenn Fairabend so the likelihood is that the Ilg Arrow, and probably other Arrows also came via Joe Shelton, as getting one by any other route in the very early 1950s was next to impossible, similarly with Dooling motors.

The restoration: With something like a two-month gap between starting to renovate the cars and establishing the identity and provenance of the Dean car, some rapid rethinking was required. I had already made a correct Arrow tank and fuel cut off as well as fitting the Fairabend axle, but now there was no way now that I could put it together as a generic Arrow, it had to be as close as possible to when it raced regularly but how to achieve this? The front suspension was missing, but it did not always run with this, so should it be re-engineered or stick with the Fairabend axle set up that came with the car, as that would be original? No question for me, original every time, but what had happened to the front suspension system?

Paul did have a Dooling with a magneto that came with the collection, but as Jim Dean’s article in 1953 explains, for the Arrow, he had to make a special, high efficiency magneto to fit the restricted space. Paul’s was for a Moore #12 car with a gearbox so could not be made to fit. Finding a Dooling 61 with a mag for an Arrow, an expensive pipe dream, so it has to be the ex speed motor for the time being and hope I can recreate the magneto. Even this is not simple, as the magneto Jim described in the article is completely different to the one he used in the car. Another oddity of Jim’s cars was that the operating arm for the fuel and ignition knock-off went through the side of the body, in front of the motor, where the ignition switch was also situated. These were operated by a complex system of levers, cranks and links, but with no idea of what he hung it all on, another aspect of the renovation that would take some serious head scratching. The standard car could be finished relatively easily, just an ignition system and a fuel shut off, but no evidence as yet as to whom this car belonged to, it certainly was not Jim’s and may not have even been from a British competitor? That was put to one side so I could concentrate on Jim Dean’s bobtail with all its history.

|

With the photos available, it was obvious now how the brackets of the fuel tank were fitted, so that could be shoehorned into the car. Another, plunger style cut off to match the tank outlet was made and then the problem of how it and the ignition switch were operated? Luckily, his standard Arrow had the same system fitted, so a side on photo in MM allowed me to scale some basic dimensions and geometry of the set up. When I found that Jim was an electrical design engineer it seemed likely that the components he had used were from commercial switchgear of the time, so there was little option but to fabricate it all. It starts with a plate that picks up on the back of the engine that is then curved to clear the cylinder and finally bent at right angles for the switch. The knock off arm goes through the side of the body and pivots on this plate with a lever that then operates the switch and fuel cut-off through three more levers and wire linkages. Having drawn it all out to get the correct relative movements but no real idea as to how it was all put together it was all down to some ‘best guess’ engineering. |

|

After two weeks of figuring with short bouts of sawing, filing, turning, and even some riveting, it was together. Well, it worked, but far too stiff to be safe, yet the solution proved to be simpler than I dared hope. The plunger on the fuel cut-off was a tad too long, and with that shortened, the whole system was far more positive and easier to operate than I had expected.

|

|

| Ignition and fuel 'on' | Ignition and fuel 'off' |

The magneto remains to be tackled, but until such time as I find a suitable donor then the car reverts to glow plug ignition. From the six pairs of wheels in the boxes, there was a pair of Doolings with C&R tyres and a pair of fronts with three screws as in the photos, so the car does match how it was set up at some of the races. Otherwise, it was a case of searching through the bags of bits to find suitable screws for holding everything down, with just the odd BA threads to confuse the situation and a bit of general tidying up. Luckily for me, given my love of bodywork, there was a new and uncut seventy year old moulding that required trimming to fit, along with studs for the hold down wires and an exhaust stack, a relatively short job by comparison. The 1957 photo shows evidence of a Dooling decal on the tether side, which is a late addition?

|

|

|

|

What then started as a speculative winter project has turned out to be so much more and not far from a ‘holy grail’ find. Unfortunately, it is not in ‘as run’ condition, which would have been an absolute dream. Even so it can now join a relatively small list of cars from Britain that do have a provenance and just one other with a European Championship to its name.

There is yet another twist to this tale that has only just come to light. Trawling through a number of photos sent to us many moons ago were several of what we have now discovered to be Jim Dean's 1956/7, 5cc Dooling powered car. Contacting the then owner to pass on the good news of the identity of the car was tempered by him revealing that he had sold it just a few months previously, but at least we now know that three of Dean's cars are still in existence.

Thanks to Philipp Meier and the Swiss Model Car Club for the use of images, Roland Salomon and Lyndon Bedford for additional images, Neil Warne and Paul Goodall for their part in the discovery, David Giles and John Lorenz for information about the US connection.

©copyrightOTW2022