|

Home Updates Hydro's Cars Engines Links Contacts Contact On The Wire ←Previous Page |

2-Stroke Maestro

Dickie Philips, Stan Clifford, Ken Hyder, Frank

Waterton

Even by 1949, Stan had realised that the two stroke motors were going to eclipse the heavier and slower revving four strokes, but while ‘Blue Streak’ was going so well he was happy to ponder on his next venture before making decisions as to the route to take. Even at this stage, he had given thought to some fairly radical ideas and he was about to embark on the most innovative and successful period of his building and racing career. It was obvious that the power plant of his new boat would have to be a two stroke and again it was fellow club member Ernie Clark that was to be the catalyst. He was producing castings for a 30cc version of the McCoy racing engine, which in his own ‘Gordon II and III’, and Bill Everitt’s ‘Melody’ were wracking up the regatta successes and records. Stan started work on the motor while he mulled over possible designs for the hull. It was not going to be conventional, and initially he considered a Dural tube frame with aluminium sides and bottom. What he ultimately produced was the most elegant, sleek and groundbreaking design imaginable that was also to prove immensely quick.

The new boat would require a great deal of time and effort to complete as everything about it was new in tethered boat terms, design, method of construction, material and fitting out. During this time, Stan and his family moved out to Potters Bar, with Stan joining the St Albans ME Society. All this left little time for racing and so ‘Blue Streak’ made its last appearance at the St Albans Exhibition before being broken up, with the motor being advertised for sale at £15 during August 1955. Mr A.M. Balling of the Baltimore Powerboat Club, a steam hydroplane enthusiast in the US, purchased the engine.

|

‘Blue Streak II’, as the boat was initially referred to, made its debut in 1956 at the St Albans regatta and created an immediate stir. There had been boats of similar style, where the sponsons had been faired into a very streamlined hull, but what was so different about this boat was the choice of materials. Instead of ply, balsa or aluminium as was originally suggested; Stan had chosen to use GRP. Right: St Albans 1956 |

|

|

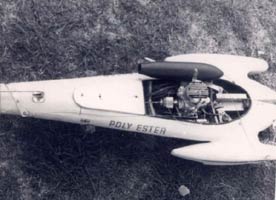

This was a leap into the unknown, both in terms of the shape and strength, although Dickie Phillips and Ken Hyder, also from the St Albans Club, would both experiment with the material for their 10cc boats. What Stan ended up with was a wonderfully elegant and streamlined design. The motor had already been proven by other competitors, yet Stan added a degree of complexity to the installation, with two batteries, various electrics, oilers and mixture controls. The drive was through a cardan shaft to a conventional propshaft and skeg, bolted on to the transom. A beautifully made manifold and expansion chamber was connected to an exhaust and tuned silencer that almost reached the transom. The flywheel was a masterpiece of engineering as the starting cord groove had a clutch arrangement so that the engine was free to run while the cord was still tight in the grove.

|

|

|

| St Albans

International 1956 with Gems Suzor in foreground |

Pauline Husbands,

Stan with Polyester, Ted Blacknell and Len Lara |

Stan at the

presentation, 1956 International, St Albans |

It was inevitable that with so many new features being applied at once that there would be teething problems, and so it proved. Firstly, the engine was immensely powerful which led to the cardan shaft regularly parting company and the skeg snapping. With such a sleek hull, there was little to hold on to when launching, and getting these big 30cc boats away with their huge props was always a problem. Stan continued to run his boats, clockwise, which was largely abandoned when surface props became popular, as he preferred to launch left handed. The first, and most obvious changes were the addition of an ‘A frame’ launching handle across the rear of the boat, and a shorter, more conventional silencer attached directly to the motor. It did not take too many outings before ‘Blue Streak II’ was faster than its four stroke predecessor, but very quickly regatta reports stopped using this name and started calling the boat by the name which it is more commonly known 'Polyester' after the resin used in its construction. The name actually appeared on the boat as POLY ESTER.

|

|

Stan Clifford continued to experiment, especially with the motor, as he was convinced that the rotary disc valve system in use on every other racing motor could be improved, either by changing the simple needle controlled venturi, or getting rid of the disc completely. The position of the motor was changed to move the centre of gravity, which involved a different mounting system with frames bonded in across the hull and the installation was simplified somewhat. In this configuration the boat would run at about 55 mph, but was well short of the 70+ that the A class boats were capable of. Left: 1958 with major modifications and new silencer |

The 1957 season was to show the potential of the boat as Stan work throughout year to iron out the problems. By the time of the Portsmouth regatta, held very late in the year at the Ornamental lake on Southampton Common, 'Polyester' produced a run of 68.18 mph for its first win. 1958 though, was to see all the hard work on this radical boat come to fruition. At the Forest Gate regatta, 70 mph was exceeded for the first time, although not for a complete run.

|

By the International Regatta at St Albans, 'Polyester' was into its stride with runs of 71.1mph in the Speed Trophy and 72mph in the International. Model Engineer commented that ‘it is to be hoped that he can go on to break the A class record, held by George Lines and ‘Big Sparky’ at 74.3mph’. Right: St Albans 1958 |

|

At the October regatta of the Blackheath Club on the Princess of Wales Pond, he did just that. ‘Polyester’ put in a superb run at 78.6mph to beat the existing record by more than 4mph. Once again, Stan Clifford held a British record, 32 years after having set his first, and a world away in terms of engine design and hull configuration. This run would also win class A in the Model Engineer Speedboat Competition, 34 years after his first success in this annual award. The following year Stan travelled over to Govieux, just outside Paris where he finished 4th overall at 76.62 mph, and was the fastest 30cc by a long way.

|

|

|

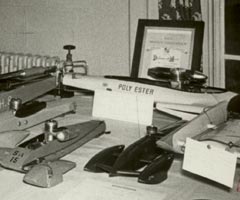

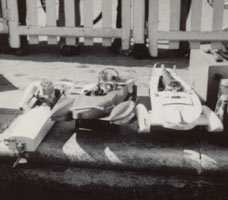

| New 'drawer handle' and silencer | St Albans Exhibition | Running at Victoria Park |

|

The boat was now running consistently in the high 70s, yet Stan was still trying new intake systems to improve the speed still further. At some stage, the boat gained its most noticeable addition, a very large ‘drawer handle’ to make launching easier, but doing nothing for the looks. Stan’s boats were regular exhibits in the St Alban’s Club exhibitions, and ‘Polyester’ was no exception During an informal club night on Verulamium Lake one Wednesday evening, ‘Polyester’ was timed at well over 90mph, although the number of laps timed has been questioned. However, at the 1958 Grand Regatta at Victoria, although the boat did not finish the run, it was timed at over 90 for the laps it did complete. Right: Victoria Park 1958 |

|

Because of its unique construction, the boat would feature regularly in technical articles, as well as the race reports. Stan entered it into the National Models Exhibition in 1960 and was awarded the Willis Cup and a silver medal. Edgar Westbury commented that "the design and finish is superlative, a result that has only been achieved by years of patient experiment and craftsmanship." The International at St Albans in 1960 turned out a non-event, with 'Polyester' chugging round slowly on the first day, and refusing to start at all on the second.

At the 1961 International the engine suffered some damage on its first run and as a result, was well below par on the second. He was also working on new ideas for engines and another hull design. The more radical design was a horizontally opposed two-stroke twin with a whole range of possible fuel induction systems he had come up with, and most unusually, the motor was intended to be water-cooled. Having made the patterns and machined most of the internals, designed the new hull and accessories, the project was dropped with no explanation.

|

|

The reason only became apparent when the crank and cylinders of the engine were measured recently. Stan had covered dozens of sheets of paper with calculations of bore/stroke ratio, piston speeds etc and then decided on a suitable bore and stroke, measured in inches. With the capacity calculated in cubic inches, this was then converted into cubic centimetres. He realised he had made an error and reduced the bore and stroke, but an elementary error in the conversion factor obscured the fact that each cylinder was still 16.3cc instead of the 14.74 he had calculated, putting it outside the A class limit of 30cc. Left: Patterns and parts for the twin |

Stan Clifford was not seen a great deal over the next couple of years as he moved down to Sussex on his retirement from The Metal Box Company where he was credited with developing the little key used to open shoe and household polish tins. He was still able to run his boats though as he persuaded a local farmer near where he was living, just outside Brighton, to allow him the use of a pond where he installed a pole to allow development and experimentation to continue. Although he remained a member, Stan now only visited St Albans annually for the International Regatta.

|

|

In 1964 'Polyester' appeared at St Albans, where it was noted that ‘it had several very hard seasons’, and that it had a ‘new engine of original design’. The ‘new engine’ was based on components from a Suzuki racing motorcycle, and the most obvious feature was a tuned expansion chamber down the length of the hull from the rear of the cylinder. A run of 64 mph was enough to win the Hyder Trophy and at Southampton, later in the year, the new motor was timed at over 80 mph, but with only two stopwatches present, this could not be counted as a record. Left: St Albans 1964 with Suzuki based engine. Not going well, judging by the expression! |

|

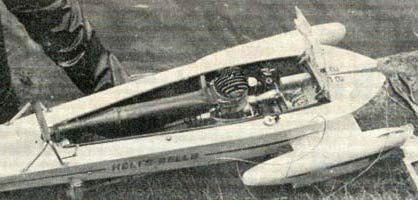

In 1966, ‘The Old Warrior’ as Model Engineer termed him, turned up at St Albans with an entirely new boat ‘Hell’s Bells’. The hull was similar in design to 'Polyester', still with integral sponsons, but this time Stan had reverted to a very basic plywood construction. The centre portion of the hull was wider, presumably to give more stability and the A frame for launching was resurrected. A hinged flap covered the inlet system and fuel tank, but otherwise it was a less sleek, plywood version of Polyester. Right: The new 'Hell's Bells' at Southampton in 1966 |

|

Perhaps the hull was too wide, as Model engineer reported, "Among the larger hydroplanes, the veteran record breaker, Mr S.H. Clifford, who never fails to achieve a spectacular performance, produced a new A class boat Hell’s Bells of which great things were expected. Unfortunately, his customary bad luck prevailed, for when the boat was travelling at a speed that was well above the record, the boat took off in a spectacular fashion and landed the wrong way up." Having gathered up all the pieces, Stan then proceeded to give a demonstration run at 73.06 mph, which was actually a winning speed for the class, although it could not be counted. Fuel injection was to be the next step with the motor to boost performance.

|

|

During July 1967, Stan made the trip along the coats to the Ornamental Lake on Southampton common, where a modest run of 54.54 mph was enough to secure victory in the A class. On his visit to St Albans Stan and ‘Hell’s Bells’ finished second to Arthur Wall in the Speed Trophy with a speed of 68.63 mph, which was also quicker than any other boat in the International event.

|

|

|

| Victoria Park 1967 | The 30cc motor with a new expansion chamber 1967 | Southampton 1967 |

Now well into his 70s, it is remarkable that Stan Clifford was still coming up with new ideas to make his boats go even faster. ‘Hell’s Bells’ was scheduled for more major surgery. The integral sponsons came of and a pair of radically new ones put onto aluminium outrigger brackets. These sponsons were hollow, with air scoops on the top surfaces to channel air to outlets on the planing surfaces. These surfaces also had skirts to create an aircushion effect, almost the exact reverse of the ground effect F1 cars of later decades. The Suzuki engine was removed for reasons unknown and the motor that had served so well in Polyester reinstated.

The Ernie Clark inspired 30, now some 25 years old, was also subject to some drastic work with a hacksaw. The mounting lugs were removed and aluminium plates bolted to the front and rear housings, which in turn were rubber mounted onto frames in the hull. The induction system that Stan came up with was ingenious and did not seem to follow any known design. A large venturi divides into four separate tracts, at the end of which are thin diaphragm valves opened by suction and the gas flow. These are not reeds, as they are circular, free floating and only held in place by a stainless steel spider. It seemed that this was the area of the engine where he considered the biggest gains to be as he came up with numerous different designs for getting the fuel and air into the engine. How successful all this changes were, we have yet to find out?

|

|

|

|

| Engine as rebuilt by Ron Hankins | Four diaphragm valves | Four inlet tracts | Flywheel and clutch |

Unfortunately, the story of Stan Clifford does not have a madly happy ending. In 1968, after 50 years of marriage, his wife Maud died. He did maintain contact with some of his long time friends and allies, but after a competitive career that had lasted 45 years he faded from the scene, as age and ill health curtailed his involvement with tethered hydroplanes. Eventually he had to give up his home and workshop, and move into sheltered accommodation. All his boats, engines and equipment were dispersed to other competitors or model engineers. His last few years were difficult as his health deteriorated badly and in 1984 he died at the age of 88.

|

Happily there are still a few artefacts to connect us with, this wonderfully innovative designer and builder. Amongst the Fred Westmoreland archives were some original photos of Stan dating back to the 1920s. All the drawings and calculations relating to the abandoned twin engine, along with the existing parts, surfaced on ebay via a roundabout route. Amazingly, ‘Hell’s Bells’ and the original 'Polyester' motor have survived although an attempt to run the motor at some stage resulted in catastrophic internal failures. The hull was stripped out some 20 years ago and a start made on removing the paint, with a view to the boat being restored but sadly, that was as far as it got. Now the engine has been rebuilt and the hull restored to the condition it was when Stan last ran it in the late 60s. |

|

|

|

|

Something else that has survived, which was common at one time but is now probably the only one in existence is an ‘engine speed indicator’ or rev counter. Many competitors used these devices to give them an idea of how fast the motor was running. Most relied on a lamp, or flag that was geared to the prop shaft and keeping count. Knowing the gear ratio it was then a matter of multiplication to get the RPM of the motor. Stan came up with a self-contained rev counter, running off skew gears on the prop shaft and bolted into the hull. With the dial facing the outside of the circle, he could see the revs directly. Having felt the gearing involved, it must have sapped the power of the engine somewhat. Interestingly, the red area starts at 20,000 rpm and the tell tail is at 22,000rpm. Impressive for a 30cc motor? |

|

‘Blue Streak’s’ motor may still exist somewhere in America, but otherwise nothing further is known about any of Stan’s boats or engines. Trevor and John Wesley did build a sister boat to 'Polyester', but what has become of the hull or motor is not known at present. As reported earlier though, the set of moulds for ‘Polyester’ that they used did survive, enabling a near replica of this beautiful boat to be created, which will sit alongside a restored ‘Hell’s Bell’s as a tribute to Stan Clifford and all he achieved. |

|

OTW would like to express its sincere thanks to

the following for providing information, results, photographs and hardware:-

Peter Hill, Jim Hampton, Norman Lara, Stuart Robinson, Phil Abbot John Wesley, Tony Pilliner, Rob Bamford, Steve Betney,

Westbury Family archive, and John DeMott. Special thanks to Ron Hankins for

rebuilding Stan Clifford's 30cc motor.

©copyrightOTW2010