|

Home Updates Hydros Cars Engines Contacts Links Part I Contact On The Wire |

A W Martin, Regattas & Competition

|

From a spectator point of view, the regattas offered entertainment and not a little excitement. Acrobatics were commonplace, as were soaked spectators. For alongside the bank was the favourite place for a boat to disappear. Each boat made its own music, that of some of the two-strokes being quite beautiful. However, when it was the turn of a ‘water otter’ – as flash steam boats (and their owners) were known, this was the time for everyone to crowd to the edge. For while the petrol driven boats usually settled down to a steady speed, either fast or slow, this was seldom the case with the steamers. They ‘wound up’ –going faster and faster, to then either blow up, dive under, or simply run out of steam, as they say. Add to this, the rising crescendo, and you will see that from the crowd’s point of view, it was a case of ‘anything can happen in the next few seconds’ – which it usually did! |

|

So that, in my time, I entertained a lot of people a lot of times. In this respect, Tornado IV was a most spectacular boat. Both to watch and listen to. Nor were the crowd at all slow at showing their appreciation, so that I know the stimulating effect of the roar of the crowd. For the mere fact that one has been able to give pleasure to so many people, also pleases you. The photo (heading the article on page 1) is about as rare as a British Guiana stamp, for it shows me with a smile - well grin - on my face. The reason? I have managed to pull off the 'Big One'.

|

It might be thought that once one had a boat that usually outshone others by several mph, all one had to do was run it, and then just wait for the prize. This was never so: for whilst I can look back now, and know that they - the others - never managed to beat me, I always had a healthy respect for them, and feared they might. For by 1939, they were very close behind in speed terms. Tornado IV had bags of power, which I dared not use. For the hull was so slow to rise that if the average for the race was between 34 and 35, then the last lap was always done at not less than 40. Also, on a circular course, any boat turned into the wind and out of it every 5 seconds at 40. As the kids might say, one just to wobble, and two to be over. So that, at 'ordinary' regattas, one did not 'turn the wicks up' as it was called, but played as safe as thought desirable: enough - hopefully - to win, but no more. One never knew whether the opposition over the previous winter, month or even week had found a new 'ginger' recipe, plus a stability, that would leave them on top, whilst yours went over. |

|

Now Victoria Park, East London, was about the diceyist water of the lot, and of course, the locals designed their boats to defeat its 'foibles'. Only about a month before, on this same water, so close was my 'guesstimating' that the boat was in the air, on its way over, as it passed the finishing line. I couldn't believe it had stopped the clock, but it had. It was as close a thing as that. This was the big day, and the weather was good. What to do? Play safe on the first run, chum, and give it the works on the second.

|

|

This was another luck day for me. For the first run went better than expected, and put the race in my pocket. Now for 'the works'. Off she went, faster than before, when 'bang! - I had no propeller. But I had WON the 'big one' (the Miniature Speed Championship) - and smiled! Just a look back at Victoria Park which was the Circus Maximus of the model boat world. It was the home of a very celebrated club and the venue of every major event. Many a boating 'duel to the death' was fought on its turbid water, often with the loser sent to a - quite temporary - watery grave. My Boats knew both the surface of the water and the bottom of it. Taken a little under 50 years ago (1936/7) the photo is not what it seems. The boat owners have been asked to pose for the press, nothing more. Now I liked all my dogs to BARK: and bark they did, in no uncertain fashion. To quote from ME ‘and the roar from its tiny single cylinder was exhilarating.’ It did do this, both to me and all the spectators. |

|

Other boats screamed or even howled, mine roared. The roar itself was a crescendo as the boats accelerated right up to the end of the race. If one couldn’t hear my boat ¾ of a mile away, then it wasn’t performing. I deliberately designed them to do just this, much as musical instruments are. It was bought at a price - of say a few miles an hour. For it was my kind of music, an orchestration that I had written myself: by such means would my boats put life into any regatta, for my music was theirs also. Speed itself is very much an impression, and sometimes ears create more impression than eyes. For a wasp without its zang is without its menace: and a dog without a bark indicates a tame dog: for such reasons did my boats make not only noise – but lots of it. From the preceding, it might be thought that Tornado IV was an immediate success. However, this was not the case, for it took about six months for it to settle down. |

|

Also, my spare time was by now very sparse. I was working at the British Power Boat Co at this time (not to get ideas, only the money) and they were so far behind with their orders that one was often required to work all through the night, and the following day! Such conditions would slow anything down, but never brought it to a standstill.

|

The old Model Engineer Silver medals, which were the accolade of the model world, had a charm of their own. It is quite likely that the original die was made about 90 years ago, and its very design - an allegory of the marvels of engineering as seen through Victorian eyes, is quite a fine example of medallion art. Now, in the Derby, it is the horse and not the owner, that wins the race: and so these medals do not so much belong to me, as to Tornados II, III, IV. For they never, ever, let me down. ‘Four Horsemen’ all lined up ‘on parade’ in the back garden of 149 Commercial Road Southampton. |

|

|

|

Two of them just hulls now and ‘out to grass’. It is 1937, and other members of the family are carrying on from where they left off. It was the fate of the latter three to be famous in their time. Not so the boat that was just called Tornado and not Tornado one. But it has my medal hanging round its bows. For in its time it was my flash steam test bed, it threw up everything that was wrong with what I was doing. For I was finding, I was feeling my way. However, it had one claim to fame. For it was the very first boat to go 'round the pole' in Southampton. It was also fast enough to have won a Model Engineer medal itself, it was me who never gave it a chance: for I was in too much of a hurry to get on, to make progress. |

|

In three years time, we as a family, would be sheltering below the very ground on which the boats are resting whilst everything around was either blown to bits or burnt to the ground. Such things are liable to happen in wars. Now one of the problems was the hull. It was very tardy at getting up on its toes, as ‘free planing’ was called. Up to about 30mph it was almost glued on the water, and if I had had more time I would have got busy on a ‘better’ hull straight away. |

|

With little time for testing, it took quite a time to find out what was the right amount of water to pump. Such a thing was very critical, for at speed the pump was making 50 strokes a second, and the quantity had to be just right, for steam that was too wet or dry (hot) gave inadequate power.

|

Last but not least was the starting problem: for when ‘opened up’ the boat would pull 18lbs on a spring balance – 2 ½ times its own weight. If released the boat would immediately somersault, for the back would get away much faster than the front. So a ‘getting away’ technique had to be worked out, a sort of circus trick, combined with some detuning. However, when all these problems were settled, Tornado IV settled down to give an almost trouble-free performance, time after time, as one can see from contemporary reports. So 1939 was quite a memorable year for me, in many ways. Now the small engine that had powered the three previous Tornados was by now just about worn out. And so in between times, a new poppet valve engine had been made. There are snags in very fast poppet valve action, so that although others thought this an excellent engine, I could only think of the problems involved: but it won many races. |

|

|

|

Both Tornado III and IV proved that they could still show a clean pair of heels, in the early post war years, and at the 1947 International they both ‘pulled it off’ in their respective classes. At the following year’s International, yet another boat – Zephyr seems to be keeping up the ‘first’ tradition. This was the only post war boat. Now it might be thought from this that the stage was all set to keep up the good work. Actually, my ‘boating’ career was very near its end, for several reasons. One of these was that, up till now, all races had been run with the boat tethered by a single attachment at the side. One result of this was that an any speed that was well into the forties, was literally an invitation to go over and under. This was even more so in the case of the smaller boats. Indeed, the problem was not so much to get the boat out of the water, as keep it on top. |

The USA fraternity had solved this by using s bridle, a fore and aft tethering. This in turn allowed them to use what was known as surface propulsion, with the prop having one blade in (the water) and one blade out. This in itself reduced the resistance by a huge amount and speeds in the 50s – 60s or more, quite out of the question before, were now possible. Only flipping, up and over, remained as a hazard.

|

|

Now, the ‘old brigade’ resisted such an alteration to existing rules, but it was inevitable. However, totally new and different hulls were now required. Yet another change was instituted at the same time. For so many complaints had been made about noise, that silencers were now compulsory. The very prospect of de-barking my dogs quite horrified me. Nor, at that time, was I able to find the time to make a fresh start. All in all, it would be better for me to gracefully leave the scene, and leave it to my very capable successors to take full advantage of the new possibilities: which they did in no uncertain fashion, with new and clever ideas. |

|

Only once or twice, in order to support my old club at local ‘open’ regattas, did I ever run my boats again. Even then my patron saint smiled, for Zephyr managed to keep up the family tradition, and come in first. It was a good way to close what, to me, had seemed to be a continuance of the most fantastic luck. Fortune had smiled on me. I would imagine that this photo was taken on Southampton Common on my very last appearance at a regatta. I must have won, for I am holding a cup I became very familiar with - the Scott-Paine Trophy. |

|

Other Activities

|

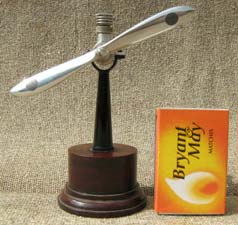

Now that does not look a bit like a boat - which indeed it doesn't. Also the photo was not taken at the time it was made, but nearly 40 years later, in its dotage. It was made around the end of World War 2. when toy shops as such did not exist, so that there were none to sell. So that, when Xmas was near, there was hardly a workshop in the country that was not producing the ‘unseen’ as well as the seen. Not that this was of any help to ‘yours truly’. For it was my job to see such things did not go on. By a strange coincidence, it was about this time that my eyesight started to fail! No, my work had to be done at home. |

|

Single cylinder inside the frames geared down, 8" long and weighed just over 1-½ lbs. Ran for about 40 mins, and cover around 2½ miles on one filling. 24ft of rail was made from National Dried milk tins in about a fortnight’s spare time.

Near to the end of what had seemed to us a long and weary war, strange tales were filtering out. One of these to the effect that the Swiss were selling tiny engines that ran all by itself, without the need for an ignition system! Such a thing was quite marvellous, for it would open up an entirely new world – as indeed it did.

|

|

Just like Toad, in Wind in the Willows, I could think of nothing else – that’s for me. There was no technical information other than that it ran on ether and the compression ratio was 16:1. It was enough to have a go. Within a week or two, the engine, perhaps the very first made in Britain existed. After sorting out suitable fuel, it ran. I could make them. All I had to do, was to find out – how big, and how small? It would only take time. Next move was to make a 1cc engine, which I thought was quite handsome. So did H.P Folland, to whom I demonstrated it. He was quite fascinated, even though it blew all the papers off his desk. Also when I confessed that I had carved the prop from the firm’s Jabroc, he didn’t turn a grey hair. |

|

Wanted to make a really little one. It took a lot of time, and a lot of care and around 100 hours work. Now is it, or was it the smallest one in the world? 0.1cc, 1 inch high and 6grm weight. Almost certainly a candidate at the time and would run to 18,000 rpm on a 4" prop. Seen on right with a standard spark plug for comparison. For a considerable period of time Bert served Secretary of Southampton and District Model Engineering Society, with fellow flash steam enthusiast Fred Marsh as his assistant. Now this makes quite a change. For it shows quite a number of excellent models that I DID NOT MAKE, for they were the work of others. The date is the very early fifties. |

|

|

|

However, I must introduce the actors on the stage. In the model world they are the crème de la crème. We see, first on the left J.N. Maskelyne, who knows locomotives inside and out. Next to him is George Thomas, a very capable engineer, and for whom I worked for many years. Next is Edgar Westbury, perhaps the best all rounder and designer the the ME ever had. Then myself ‘with piecing eyes and hollow cheek’ as Shakespeare might have put it. Lastly is one of my Vickers pals, whose name has gone. looking back I would give the following advice - if asked to act as a judge, always refuse. Football refs are nice people by comparison. |

|

Now with age comes experience, and just a little more idea of what to look for: also, if one is repeatedly given publicity, one gets a reputation, whether one deserves it or not. 'Of such things are clay idols made.' Did I say that, or was it someone else? So that when one is given the title Judge, and is doing it for the first time, there is no doubt that one can only be feeling one's way, possibly with less dramatic effect than say, a surgeon doing his first operation. However, just doing it brings its own experience and there was no lack of that: for there were many exhibitions of models, and judging was always done by outsiders. |

|

Finale:-

I have told of how the first button was pressed. I didn’t just dash off and make a flash steamer for I had never made one before, and there was a lot to find out. My old friend Vic had most of the old Model Engineers giving accounts of the very boats I have mentioned. It was manna from heaven. Now to me, there was romance about those old accounts. In some way, the very enthusiasm, not written in the text, but between the lines, was rubbing off on me. I just had to carry on where they left off. It was all building up. But there was still the ‘it can’t be done’ hurdle. Now there is, and always was, an energy world of entropy, a strength of material in ultimate terms, a fatigue factor. Perhaps fortunately for me – for fools often go where angels fear to tread – at that time I knew nothing of the mathematics of such things, however useful they became at a later stage. This may seem strange: but what it means is that if I had used such a calculation approach, based on what was thought to be the factors, I would have only come to the same conclusion – that it couldn’t be done.

Now, over the previous years, I had made a great many tiny engines driven by steam. I was not kind to them, but pushed them to the limit, and beyond it. I knew the power of steam by the very feel of it, plus a fair idea of how much metal to use, based entirely on a ‘that looks about right’ assessment. In Disney terms, I was not so much a scientist as a 'Practical Pig'.

From such unlike beginnings was the first step made. Only to immediately run into the same kind of failure that had beset everyone else. However one looks at it, it was my good fortune that things immediately failed, for it was a start on my ‘that looks about wrong’ outlook on flash steam stress and strain. By such a method does nature itself design things in the long run? Also I was getting my priorities right: first survive, then perform. For it was by the enforced manufacture of such a key, that I was able to break through the ‘it can’t be done because’ barrier. From subsequent events, it would seem that this part of my education was hammered home – by failure – better than any teacher could have done, either by kind words or a cane. For in a very short time, my plants were free of trouble, other than in a very minor way, over all the years I was in the game. This in a world where high performance was the name of such a game, and trouble was everywhere.

|

|

|

| 0.1cc Miniature Diesel 60+ years on | Tiny, but immensely powerful and successful flash steam motor. | |

To be written up in the history books must be one way of achieving posterity, yet here we are in Experimental Flash Steam (John Benson & Alan Rayman 1972) and with some very flattering remarks. Perhaps the single comment that gave the most satisfaction was as follows ‘-as far as is known, not a single one of his boats ever suffered a mechanical failure whilst racing (referring to engines) No higher compliment could ever be committed to paper.

There was more to our sport than simply running boats. It served to bring together people who got on with one another, who understood one another. And so to look back is to remember friends, a great many of them, first, and then the boats: in that order. And how better to end?

Update:- In conversations with Tony he was very concerned that there was no museum that would be prepared to accept his father's archive material and items from both his work in the aircraft industry and flash steam. We were delighted when Tony contacted us with the news that after protracted negotiation, the Science Museum in London, would take all the material. This was a first as they have always refused such approaches in the past.

| A.W. Martin | |

|

|

Bert Martin died in 1994, but left this amazing piece of work that not only documents his remarkable contribution to the development of flash steam tethered hydroplanes, but also says so much more about the people involved during that vintage period. One incident related here by his son Tony, sums up his entire approach. ‘A final thought. My father mentions appreciating the roar of the crowd just like his son Frank. Frank was a successful athlete over many years. Dad trained him up to be national youth mile champion. Someone made the mistake of responding to Dad when Dad said he would look after Frank's training during the school holidays. "Who do you think you are - you are not a proper coach!" Dad lapelled him & said "Listen carefully I'm taking Frank to the top!" And he did! He worked out the best method & applied it just like he solved engineering problems.’ |

We are indebted to Tony Martin for allowing us to publish this unique insight into his father’s work and for all the help, information and material he has provided. Additional photos by courtesy of the Westbury family

©copyrightA.W&TMartin2009