|

Home Updates Hydros Cars Engines Contacts Links Racing Contact On The Wire |

The 'Airscrew Page'

Renaissance

The arrival of carbon fibre B1 boats from Bulgaria through Norman Lara, has encouraged even more interest in the airscrew classes that has already been growing over the last few seasons. What is not generally realised is that airscrew boats were not recognised by the MPBA until 1968, making this the 50th anniversary of the F Class becoming an official class in Britain. These 2.5cc airscrew driven boats had been part of NAVIGA for many years but because of a blanket ban by the London County Council and consequent lack of recognition from the MPBA had not been allowed to run legally in this country. That is not to say that there had not been numerous examples running since early in the last century. Where these ‘hydro gliders’ differed is that were usually quite large motors, up to 30cc in some cases or even pulse jets, mounted on equally large hulls and run free. One example had a McCoy 60 on top, so one can appreciate the reluctance of any council or the MPBA to allow these officially. There were numerous commercial kits and published designs for smaller airscrew driven boats, many of which still turn up on ebay. Vic Smeed in particular tried to popularise these, lobbying the MPBA to accept them.

|

|

|

| Hydro Glider | Czech Bi line up | Jiri Baitler's design |

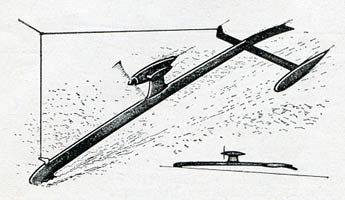

On the continent, primarily in Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria, they had developed in an entirely different way, having tiny sponsons and even vestigial wings to keep the equally minimal structure out of the water. Allied to the extremely powerful 2.5cc speed motors that were available, the world record was held by Georgi Mirov at 95mph. Werner Papsdorf of East Germany won the first B1 European Championship in 1963 at 105kph, the last time the B1s were slower than the A series boats.

|

|

By 1967 and the European Championships in Amiens where Mike Drinkwater competed, the hulls were recognisable as what are still in use today, although there were several variations on the theme. There were twin booms with a single plane, twin booms with steps and a flying tail as outlined by Mike Drinkwater in his article he produced for OTW and twin front sponsons and a flying tail. The configuration that was to become the norm was the single boom with a riding plane at the bow and a flying tail with two small sponsons at the rear. These were in common use by Horvath from Hungary amongst others, but it was Jiri Baitler’s ‘proa’ style boat with a single tube hull and one outrigger that proved hard to beat. In Amiens, Baitler from Czechoslovakia won the class at 182kph with Mike Drinkawter 6th at 140kph. Left: Matchstick in foreground |

|

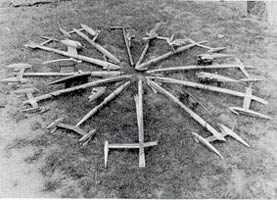

After lobbying following the return of competitors from Amiens, the MPBA relented in 1967 and established the F Class for 1968. Mike Drinkwater demonstrated the class at regattas, using no less than five boats on one occasion, including ‘Matchstick’, his take on the Baitler design. Mike set the British F Class record with this boat at 108mph (173kph) while Baitler won the Europeans at Russe in 69, the first time 200kph had been exceeded in the competition. Right: A selection of Mike's boats including fearsome pulse jet Once the class was established the number of competitors in Britain soon grew with Mike, speed flyer Ray Gibbs who used the Carter Special from his speed model, Pauline Husbands, and Pete Hough competing abroad regularly. Jean Peidnoir who also won the European Championship in 1973 wrote articles for Model Boats in 1974 describing alternative designs, which engendered even more interest in this country. Trevor Biggs, Jim Free and Ian Mander amongst others were all trying to match the best of the continentals. |

|

Mike produced a number of kits aimed at beginners, whilst Ian Mander started to supply a few top of the range boats as the F2A technology he was so involved in played a large part in B1 design and construction. Several A series competitors dabbled, especially in 1975 when the Championships came to Welwyn. A boat imported from Russia with a very rare Kostin motor became the fastest B1 in this country, although the record was never claimed.

|

|

| Hungarian 'Baitler' boat with aluminium wing rather than bridles | Conventional boat with part wing of carbon |

Speeds continued to rise through the 250kph mark but there were inherent problems, firstly ensuring that the craft was a boat, Ie. it would float when at rest, and touch the water at times each lap and more problematic of all, meeting the noise limits set by NAVIGA, which they regularly failed to do. Siggi Grasshoff won his European Championship in Amiens with an old Rossi powered boat simply because it was silenced and ran. On occasions entire runs have been completed with the boat feet off the water, but it is a contentious issue that has yet to be satisfactorily resolved and verifying whether a boat has touched the water at 280+kmh is far from easy.

|

|

|

| Silencer stiffled performance | Sprung loaded 'washer' plane | Fixed front plane |

The single boom hull with a planning step at the front and a flying wing with two small sponsons or tappers is now standard although all sorts of alternatives have been tried, the oddest being a single front planning step set below the boat and even sprung in some cases.

|

|

| 'Tappers' | 2.5cc Proffi speed motor |

With a Proffi, Kostin, Kalmakov or similar motor, B1s are capable of well over 260kph. We did see Pierre Barbotin and Anna Karavayeva both record identical speed of 267kph in France while Jim Free holds the British record at a shade over 250kph.

|

|

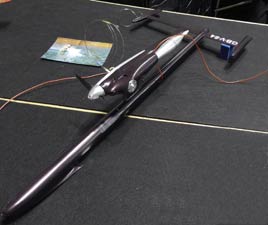

| 1970s East German B1. Planes front and rear. Rossi motor | 2017 Bulgarian production boat |

After far too many runs were voided in Championships, NAVIGA relaxed the noise limit on all classes putting restrictions on exhaust sizes instead, but this put British competitors at a distinct disadvantage as they still had to run with silencers in this country. The need to use silencers did see interest waning until a decision was made to adopt the same exhaust outlet rule. Rick Neal with one of the new Bulgarian boats has already exceeded the British record, but only in practice, and with several all carbon boats now in the country, a new record could be in the offing.

|

In Britain a second airscrew class was introduced B1R (restricted) with a view to keeping costs down by setting a relatively low price limit on the motors that could be used, still less than £100 with the most popular and fastest being the MDS, available from £25 upwards as against the £400-£600 for a Russian 2.5cc motor. Restrictions were also placed on the propellers and materials that could be used in the construction of the boat. The materials rule was relaxed so that the same hull could be used in both class, now renamed B1S (sport). Even with the cheaper engine option, the B1S is no slouch, with Jim Free regularly recording runs over 120mph. Right: MDS powered B1 Sport |

|

There is one last airscrew class in this country and that is for Vintage boats, designs and motors that predate 1963 this includes many of Mike Drinkwater’s early boats, several of which are still in existence.

2018 saw three of the fastest

runs recorded in this country for over a decade and two of them with a British

engine produced by top speed flyer Pete Halman.

Unfortunately, conditions have rarely been suitable for running these boats this

year so Jim free can breathe a sigh of relief as his record remains intact for

another season.

B1 & B1 Sport. WHAT'S THE DIFFERENCE?

On first glance both of these airscrew hydroplanes are very similar. They are both powered by 2.5cc engines, are both about the same weight, the engine mounting being the most obvious difference. One being a side mounted set up, the other being inverted. They are in fact quite different when it comes to power, speed and most definitely cost.

Let us first take the boat at the bottom. This is the open class B1 hydro, built from quite high tech materials such as carbon fibre, Kevlar, alloys of one sort or another, with some lime and balsa. The whole thing is covered in epoxy. The power for this boat comes from a Russian made Cyclon TOP 2.5cc engine costing some £500. Competition fuel is 80%-20% methanol, castor oil mix. For the top boats in the class, speeds of 160-170 mph can be expected.

The top boat is quite a different kettle of fish. This is the B1 Sport where certain elements are "RESTRICTED".

What are these restrictions?

The first thing to remember is that this class is mainly aimed at the beginner in the sport. Materials used in the hull construction are now free, but all parts must easily obtained commercially via local model shop etc. The engine is the area where costs and performance are controlled and has a maximum price of £90, which is reviewed annually and must not be modified. However there is now no restriction on the fuel used . The record for the B1S Class, is now a tad under 130 mph. So there you have it, two boats that on the surface look very much the same, but that are quite different.

Thanks to Jim Free for this description of the two airscrew classes

Mike Drinkwater's sixty years of airscrew hydroplanes

|

|

Halcyon days on the water by Mike Drinkwater In November 1954 an article was published in "Model Maker" featuring my tethered hydroplane "Ballerina". The elements making up the design had been developed through a series of models during the preceding years. |

In 1948 I was running my home built fast electric boat on the park lake during the school holidays. Two young men appeared with a free running hydroplane powered by a Mills 1.3cc turning a 10" airscrew. It had two floats based on the shape of the Schneider Trophy seaplanes.

My friends and I wanted something faster. It would have to be lighter and travel on the surface of the water. I designed a small rectangular boat for an E.D. Bee. The underside of the hull was flat side to side with a step and a 3 degree planing angle. That figure came from the work of the eminent Victorian scientist Froude. Chasing the model around the lake kept us very fit!

|

The same year I built a kit of the delightful little Frog "Whippet" waterscrew hydroplane for a Frog 160 glow. The following year the E.D. Challenger kit was on the market for the E.D. Competition Special. Although it had the advanced features of a two point bridle and a surface piercing prop, as a working model it was hopeless. In 1949 I purchased the more powerful Aerol "Hurricane" 2cc for £1 15s. A new boat was designed and built. It was larger than before the original and had lightweight wheels at the front and rear on the port side. It ran clockwise against the wall of the lake, because we knew that the torque of the engine in tractor configuration would tend to turn it in. |

|

However, it was much too fast to handle so it was decided to try it tethered to a central pole. The wheels were removed and replaced by an arm extending from the engine mount, in line with the balance point of the boat. The winter had arrived and the lake was frozen so the model had to be run on the snow. This was no hardship since I didn't have any waders! It accelerated fiercely and looped almost immediately due to the air pressure beneath the front of the hull.

In the spring of 1950 a larger, slimmer model was built with a tunnel hull for the Frog 500 turning a 10"x8" green 'Truflex" propeller. Experience with control line aircraft had shown this to be a remarkably effective combination. To run the boat, the operator stood in the water holding the line, so that he could step back and keep the line tight. This was done to counter the problems I seen at the Altrincham Club. Some members, who were running 15cc and 30cc waterscrew hydroplanes, had endless trouble with their heavy linen tethers dragging in the water at the launch. On the first run the model accelerated rapidly and promptly looped after about half a lap, something I should have anticipated.

To counteract the effect, I built a small model with four sponsons so that the airflow would lift the back as well as the front. It ran clockwise around a pole with an Albon "Javelin" turning a 7"x6" airscrew, at 37m.p.h. A photo of this model appeared in "Model Maker".

In 1951 I drew up two new designs. The first model was very simple and used the powerful Elfin 1.8, whilst the second was a more complex asymmetric design. I was concerned that the first model would loop (although with hindsight I realise it would have been safe) and I opted for the second. This model was also shown in the magazine and was powered by an Elfin 149. The layout was again intended to counteract the weight of the tether, probably not necessary since I was using 42' 6" of button thread. For the first time a three line bridle controlled the directional and lateral stability.

On the same model a rear horizontal aerofoil was fitted, set at a slight positive angle, to prevent looping and hopefully, by raising the back off the water, eliminate a source of instability. The first run was a revelation; the back came up and held absolutely steady and the speed rose to a very unexpected 53mph.

Two years later, after National Service, I went to Stamford Park in Altrincham to see "Faro" running. It was magnificent! A thundering motor powered the model around at 55m.p.h with a great "roostertail"; I was very impressed. I didn't even bother take my own little boat out of the car.

In 1954 it was back to the Frog 500, also mentioned in the "Model Maker" article. Fairly large, it was the first time I used the single front sponson layout. It launched easily and ran well at 75m.p.h, attached by a strong steel line.

|

Based on the success with this model I designed a second model, this time for an ED Racer. This was "Ballerina" and the drawings and photos were published in the November 1954 issue of "Model Maker". The Editor, Vic Smeed, asked readers not to be alarmed by the speed of 70mph. It had a compact lightweight structure, a single front planing surface, a lifting aerofoil stabilizer, a reliable bridle system and it ran clockwise. I had selected a 2.5cc motor specifically to moderate speed. |

|

In the July’ 55

issue of "Le Modele Reduit de Bateau", in a short article on "Ballerina" the editor suggested that it might be 'une idee de recherche qui n'exclut pas la fantaisie". That was how it came to be generally regarded, as an item of fantasy. I was away at college during these years and no-one else had the experience to run such a model.Nor was an air-control device yet on the agenda for full size hydroplanes. In 1956 I met Donald Campbell at Metropolitan Vickers in Manchester, where I had worked, to put to him the advantages of a rear aerofoil stabilizer. Early the following year I was sent to see the Professor of Marine Engineering at Newcastle University. He introduced me to a Research Graduate who had worked on John Cobb's "Crusader". They were all very polite, but what I was saying didn't register.

|

|

In 1958 I went back to producing a small free running airscrew boat for the youngster who lived next door to my student accommodation. We ran it on the local Paddy Freeman's pond in Newcastle. It was a strong, attractive little model, so I sent the drawings and a studio photograph to Henry J Nichols. He produced it as the "Mercury Hydroplane" kit and exhibited it at the Earls Court Boat Show. The kit sold in the shops for the next twenty years without ever being advertised.

|

In the early 1960's I made another attempt to popularise tethered airscrew hydroplanes. Again I considered two alternative designs. The first option was to build an asymmetric model with an outrigger on the port side, to counteract engine torque. It would have been the more efficient of the two and in retrospect could well have reached 100m.p.h using my powerful K&B 19.

|

The alternative which I chose, was the twin float layout, which modellers had been familiar with since the time of float planes. I built "Axilla" and "Lindoh" featured in "Model Boats" magazine. They became popular, but twin floats were a developmental dead end and faded out by the early 1970's.

|

|

In the meantime, these cheap, reliable models were beginning to win "Fastest Time of the Day" at Model Power Boat Association regattas. In 1964 the Council of the MPBA wrote to inform me that from then on airscrew hydroplanes were banned from their competitions.

The ban had to be lifted in 1967 in time for the first World Championships at Amiens in France. Naviga had introduced Class B1 for 2.5cc airscrews and the Eastern European Teams entered B1 with some very advanced and fast models.

Following their lead, in 1968 I made the asymmetric model which clubmates named "Matchstick" (I never liked the name) to set the first British Class F record at 108mph. We ran at Keighley Tarn, high on a hill, in the lee of a dry stone wall.

|

|

I entered very few competitions in the 1970's and

80's, but in 1998 I had an unexpected class win with my 'Comet' design

at the Amiens International Regatta. It was designed to be an easy to

build model with easy handling. I distributed copies of the drawings and

sometime later I saw the French Juniors from Poitiers, on a visit to

Farnborough, all holding models very similar to 'Comet'. In 1999 'Comet'

underwent a redesign and 'Merlin' was introduced; a few kits were made

in 2001. |

Recently I have built a model for use in club events, powered by one of the quieter side exhaust motors, to try to keep within the noise limit.

©copyrightMike Drinkwater 2008

Delta One

Delta One is a replica of a model built in 1954, one of a series of experimental designs. It was the first to use a single front planing surface, a rear aerofoil and a bridle to keep it upright and on course. This is the basic pattern followed by today's B1 competition hydroplanes.

In December 1954 Model Maker magazine Vic Smeed described the new design as 'the hydroplane to end all hydroplanes'. An alternative view, widely held, was expressed by M.Bayet in the August 1955 'Le Modèle Reduit de Bateaux'. He said it was, 'une idée de recherche qui n'exclut pas la fantaisie' (an idea of research which does not exclude fantasy).

|

|

Ten years later the Model Power Boat Association banned airscrews from its regattas as being 'dangerous and not boats'. The ban was lifted after the success of the new Naviga airscrew Class B1 at the Amiens Championships in 1968.

|

Mixed Memories of Amiens 1967Why is it we remember the crazy things that happen, rather than the sensible ones? A couple of years ago two French gentlemen approached at a regatta, laughing, to shake my hand. Someone had pointed me out as the builder of the ‘bread roll boat’ all those years before. I once heard a French spectator at the St. Albans regatta speaking to her companion “When I was a little girl, in the park at Amiens, I saw a man with a boat made from bread rolls.” By coincidence I have just received two photos of the same subject from Jacques Perrier. Photo right courtesy of Arthur Wall |

|

|

|

It seems a good joke, but it didn’t start that way. At those first, celebrated, Naviga Championships at Amiens in 1967, I was able to run my airscrew hydroplane in a competition for the first time. By the end of the week my model was going well, very well, but lack of experience saw it smashed to pieces, beyond repair. Out of a sense of despair and frustration came the ‘bread roll boat. The hull was made from a wooden placard, the sponsons were ‘ficelles’ from the local bread shop. It looked more like a scarecrow than a hydroplane. |

|

Arriving back at the lakeside, the crowd in the stands surged forward with cries of delight and dozens of cameras. At the running circle the final competition rounds had just finished and willing hands attached the model to a line. The old Eta diesel was started up, but it didn’t go anywhere. Amid cheers, the bread rolls detached and slowly floated off in line, like a convoy of ducks. At the next circle the Russians were making attempts on the World records. Nobody was paying attention to them. |

|

Many thanks to Mike Drinkwater for sharing this amusing memory.