|

Home Updates Hydros Cars Engines Contacts Links Next Page→ Contact On The Wire |

1948. The year tethered hydroplane racing changed forever

Having been in existence for exactly forty years, circular course tethered hydroplane racing was changed forever during the 1948 season by the participation and unique approach to the sport of a forty two year old production engineer from Sunbury On Thames, George Stone. Not only did George achieve the almost mythical ‘quantum leap’ in speed but also did it in a manner that ultimately ensured the survival of the sport whilst unfortunately providing the catalyst for a long and divisive argument that somewhat surprisingly is still rumbling on in the 21st century.

The sport was slowly recovering from the effects of the second war, with the MPBA having only just been reformed. Boats and engines were primarily large, heavy and traditional pre war designs although there were several examples of the newer and smaller ‘austerity class’ that was becoming quite popular. Speeds were relatively modest and with most boats being variations of the ‘kipper box’, stability was also an issue. Single bridles and submerged propellers were also the norm. George Stone came into the sport, probably through the influence of well known engine builder and competitor with hydros and tethered cars, Basil Miles from Ewell and a fellow member of the Malden Club. George had no previous experience with the sport as, according to an article in the Middlesex Chronicle, ‘he has taken up motor boat racing as an outlet to his energies, now that he is no longer engaged in high speed cycling’. Indeed George had been of such high standard that he was a former holder of the British ¼ mile tandem record and had been included in the British Cycling team for the 1928 Olympics to be held in Amsterdam. Unfortunately, a mugging in Richmond Park prior to the event meant that he was unable to compete.

|

The design for George’s first tethered hydro utilised his specialist knowledge of aeronautical engineering that he had gained in the 1930 working for Hawkers in Kingston where he lived at the time and from the early 1940s at Vickers in Weybridge, where he worked alongside Barnes-Wallis for a while. George had also gained valuable experience of high-speed boats when involved in making numerous test models for Edward Spurr’s attempt on water speed records with a revolutionary boat ‘Empire Day’. The co-designer of this project was none other than T.E. Shaw, better known as Lawrence Of Arabia. This was an ‘air cushion’ boat, not a hovercraft as such, as it relied on the airflow underneath the hull to provide the lift. |

|

It is from this background, rather than established tethered hydroplane racing that George came up with the design that was to prove so successful. The boat, which he named ‘Lady Babs II’ after his wife Beatrice, consisted of two ‘slices’ of aerofoil section separated by a small pod to contain the motor and fuel tank. The bottom of the twin hulls had a step around 1/3rd of the length at the point of maximum depth. What he had produced in effect was a perfect wing shape, with a hydroplane step.

|

|

The boat was just 27 inches long and constructed on aircraft principles that kept the weight down to under 4lbs. He incorporated the twin bridle system that had been demonstrated by Gems Suzor and was in universal use in the US and had been accepted that year by the MPBA. If the hull was unconventional, the motor that George decided to use was what was to contribute both to the success of the boat and the later controversy. |

It can only be assumed that he had decided that if he wanted to go as fast as possible, then the only option was to use the most powerful motor available, and that was the Dooling 61 produced by the Dooling Brothers in Los Angeles. This motor had already proved itself in tethered cars, but with the post war restrictions was very difficult to get hold of by any normal means.

The building of the boat and finishing had taken George just five weeks, but like many enthusiasts of the time, this represented many long hours and late nights in the workshop. Indeed neighbours mention seeing the lights still burning in his workshop at 5 am in the morning.

George Stone and ‘Lady Babs’ did not make their first appearance until Sept 12th at Blackheath, but it was to be an amazing, and to use modern parlance, game changing, debut. The meeting did not start too promisingly for him as he broke the propshaft so could not compete although he said that he hoped to repair it in time to get a run at the end of the regatta. George did manage to affect repairs, so following Daisy Vanner presenting the prizes the light line was put on for the first run by ‘Lady Babs’. Less than thirty seconds later, tethered hydroplane racing had entered a new era. The speed of 58.3mph for 500yds was the highest that had been recorded in any class in this country. For comparison, the 10cc C class at this event was won by his namesake A. Stone at 33mph, which until then had been considered quite fast for these little boats. Considering that this was the boat’s first outing George said that he planned to reach 60mph at Brockwell Park when the boat makes its second appearance, which it did, to become the first model boat in Britain to exceed 60mph.

| Stew Pond Sept 19th 1948 Basil Miles holding stern of Lady Babs, George on the starting cord and Charlie Cray holding the bow. Basil launching while Charlie deals with the glow plug lead |

|

|

On Oct 20th 1948, during runs at Stew Pond on Epsom Common for a Dufay Chromex colour film to be sent to the USA ‘Lady Babs’ did 69.71mph for 500yds setting a new British and European record, which included equalling the world’s best flying lap at 73.77mph, In addition the boat recorded 67.3mph for 1833 yards, and 64.8mph for 2749yds all timed by a system borrowed from the National Physical Laboratory at Teddington.

|

|

|

| George setting up timing gear | Basil Miles, George and Rodney watching 'Babs' | Rodney with experimental 'Babs III' |

George commented that a successor to ‘Lady Babs II’ to be called ‘Lady Babs III’, and somewhat experimental, was well on the way. The original boat still had plenty of development potential so on Oct 31st George organised an attempt on his record at Stew Pond that was to be filmed by Pathe to be released in London on 10th Jan 1949. The record attempt failed, but the film is still available on the Pathe News site, (no 226).

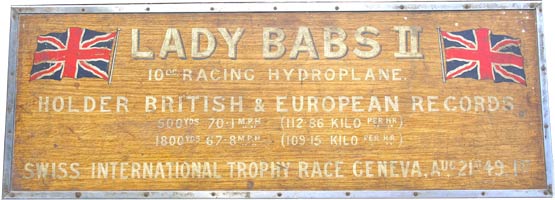

The achievements were not over for the season as another long distance run saw ‘Lady Babs’ achieve the first ever 70mph run over 500 yards in this country, backed up with the notional mile being covered at 67.8mph. These speeds were acknowledged through MPBA record certificates awarded in November.

|

|

|

|

|

A bit quick off the mark, Basil and George watch another fast run on Epsom Pond |

||

In his end of season summary, Edgar Westbury rather churlishly commented that he was ‘not sold on the new-fangled notions such as the two legged bridles and surface props’. There was no mention of George or the use of the commercial motor and another far reaching statement that it was a fallacy to consider only salient features of hull design as being important. A final slight was that ‘British competitors are running true to form in their cautious and conservative outlook.’ This overlooked completely the fact that George had broken the outright record by nearly 20mph with a boat of only 10cc and was running some 40mph faster than any other boat in that class. The annual Speedboat Competition was not open to George with his Dooling, but for sake of comparison was 11mph faster than any other boat entered.

|

George was not done for the year, as something new and exciting was afoot. Model Engineer had published numerous letters relating to tethered car racing and the rights and wrongs, not of using commercial motors, as this was by now the norm, but of using American or other foreign motors and parts to claim British records. This was obviously something that George and fellow Malden member Basil Miles were conscious of, as Basil had been building a new 10cc-racing engine designed by Charlie Cray, another Malden Club Member, and more importantly, designer of ED's early motors. It was their combined avowed intention, that before 1948 was out they would show that ‘Britain can make it’. Right: 'Babs' fitted with Prototype ED Fireball |

|

The first attempt to run ‘Babs’ with the new engine on December 28th was thwarted by Stew Pond being covered in ice. The second attempt was at dawn on New Years Eve, but before that could take place, Basil had to wade out waist deep in the freezing water to affix the pylon. The motor started easily and ‘screamed round’ to something of a record for a standing start lap at 60.3mph. The weather precluded any more serious attempts but the performance of the motor convinced them all that it represented a serious challenge to the supremacy of the American motors. Through Basil Miles’ involvement as a design consultant with ED, which had been established in 1946 at Villiers Road, Kingston on Thames, the intention was that the company would produce the motor commercially as the Fireball, with the later addition of a 5cc version. However, as far as can be traced, this never occurred.

1949

The direct result of George’s amazing achievements the previous season was that the MPBA divided the 10cc class into two. C Restricted for boats with commercial engines with a new trophy to race for at the International provided by ED and C Class for home built motors with the Wico-Pacy Trophy. Whilst the latter trophy disappeared in the late 1960s, the ED Cup is still raced for annually.

George appeared for the season with two new boats in his stable. ‘Rodney’, which was an exact replica of ‘Babs’ and named after his son, and ‘Lady Cynthia’, named after his daughter. This boat was a departure from the twin-hulled design and was modelled along the American lines with integral sponsons. In an interview he stated that the new boat was the result of experiments over the winter and with the motor producing about 1.4bhp on doped fuel expected it to reach around 80mph during a record attempt at Geneva in August.

|

|

|

| Lady Cynthia | Rodney | George and Rodney Stone with Lady Cynthia |

Indicative of the close ties between George, Basil Miles and ED was the announcement from that company in July of a kit version of the twin hulled Babs design to be called the ‘Challenger’. This was a much smaller hull of balsa construction, intended primarily for the 2cc ED motors, or at a push the larger Mk III. The hulls were much wider in proportion to their length than the 10cc boat as well as the space between them being filled through to the step. In effect it was an old fashioned bottom half with a twin hull deck. ED claimed that 40mph was possible with this boat, making it faster than any C class boat and many others besides, despite its diminutive motor.

The MPBA International at Victoria Park in July saw the debut of ‘Rodney’ alongside ‘Lady Babs’ but a combination of engine failure and accidents meant that George did not complete a single run. He later commented that the day prior to the meeting when testing the now mandatory silencers he had reached 61.5mph and the following Tuesday having received permission to run on the yacht pond in a royal park the boat managed 77.45mph.

Knowing that his boats were so much faster than any others in Britain at that time, George and his wife set out in early August on a true adventure to take in international regattas in Geneva and Paris to run his boats against the best in Europe. It was also the start of a four-year pursuit of the two major international hydroplane trophies, the Hispano-Suiza and the oddly named Ford Mechanics.

|

|

On the way down they enjoyed the hospitality of the Suzors in Paris before continuing on to Geneva to meet up with the other competitors at the home of Jean-Loius Chevrot for a party in honour of George and his wife. The deed of gift for the Hispano required the country of the previous year’s winner to host the next running, hence Switzerland as Chevrot had won the trophy in 1948. He in turn had taken the trophy from Robert Jonet who had won it in 1947. Mme Edith and Mons Gems Suzor Boulevard Montmorency Aug 14th |

The first indication that something remarkable had occurred in Geneva was a postcard that arrived at the Model Engineer office from George stating that ‘Lady Babs II’ had won the Hispano at a speed of 68.21mph, with ‘Rodney’ 4th at 58.7mph. A more detailed report showed that in training ‘Babs’ had reached 74.5mph and Rodney 68.3mph. The race was not so straightforward as it was incredibly hot making it difficult to get a needle setting, leading to the winning run only happening in round three. Jean-Louis Chevrot finished second at 62.5mph and Pierre Chevrot third at 60.1mph. After the meeting George set a new European record of 70.1mph and was travelling much faster on another run when the thrust bearing seized.

|

|

|

| Jean-Louis Chevrot | Jean-Louis, George and Robert Jonet | Pierre Chevrot |

George was back in Paris for the French International on 11th Sept on Lake de Croisey at Le Vesinet where the race for the Ford Mechanics Cup was to be held. The Hispano was restricted to 10cc boats, while the Ford was open to all classes. It was immediately apparent that there were problems with the water at the lake, which was ‘highly disturbed’ owing to a backwash close to the launching area. The pole was moved but the problem still persisted to the extent that George’s number 2 boat ‘Rodney’ piled in with the motor running at full revs, which then proved the incompressibility of water, blowing the top half clean off the Dooling motor. This was a very common fault with the thin casting of the Dooling, but nevertheless very expensive and frustrating, as these motors were still very difficult to come by. George was luckier with ‘Babs’ and ran out the winner of the Ford Cup by 9mph so completing the Hispano - Ford double, an incredible achievement.

Ist George Stone Lady Babs II 62.7mph. 2nd Jean-Louis Chevrot (Switzerland) Folbrise V 53.7mph. 3rd Jean Devauze (France) Vano 52.7mph

The 'Controversy'

It was however a report on the Geneva event in the October 6th edition of Model Engineer that was to cause the controversy which overshadowed George’s amazing success and brought down on him such an unprecedented level of criticism and comment that almost matched the Internet trolls of today. The article, written by George, was entitled The Swiss International Regatta.

|

In it George describes the event, praised the hospitality and non-austerity catering that he and his wife experienced, along with the technical aspects of the boats he was competing against. It was the last few paragraphs that unleashed the torrent of abuse though. He starts of by saying that ‘it is obvious ponds like Victoria are not suitable for high speed, and running events on them such as the International does not give a true result.’ He then tweaked the tail of much of the tethered hydroplane establishment with the comment that ‘if one wants to figure in events run on these ponds, a boat must be designed to run at speed under 50mph.’ He finishes by saying that ‘a great deal of credit is due to those who run boats and keeps the interest going. For my part I want to develop boats to go as fast as the best of them’. The article concludes with some observations about how regattas might be run after his experiences abroad and a self-deprecating ‘(after all I promoted the worst regatta held here this year)’. The last sentence repeated his reply to the toast in Geneva. "It is better to make friends than win prizes; I have been lucky in doing both." If only he knew? Right: George, Beatrice and 'Lady Babs' at Geneva |

|

It started gently enough with a letter from Mr Curtis of the Kingsmere Club questioning some of George’s observations regarding regattas, lakes and speeds but ends with hearty congratulations on his achievement. A week later however, Mr Mitchell of Runcorn goes in with all guns blazing, sarcastically suggesting George should have titled his article How I won the Swiss International and went on to state that ‘they (the Dooling Brothers) deserve 90% of the credit as they made the engine.’ He claims that the ‘dismissal of the 30cc event in two lines was to increase Mr Stone’s superiority even further.’ Even George’s mention of the hospitality was taken as a criticism of standards over here. He also rounded on George’s comments on Victoria pointing out that this ‘is an admission of defeat’. Mitchell’s final paragraph would reasonably be taken to be highly tinged with sarcasm, which invoked a detailed response from George the following month.

|

|

|

| A series of photos from Geneva | ||

Ernie Clark from the Victoria Club waded into the fray in mid November with a long letter, the gist of which questioned everything that George had said and done. He laid his cards firmly on the table saying that all of the credit for the successes should be given to Doolings and none to George. If this was not inflammatory enough, he concluded with a statement that may well have found favour with a certain element, ‘if you haven’t made it or it isn’t British, don’t take credit’.

In a long letter on December 1st George replied, starting by noting ‘a certain bitterness and scorn’ in Mitchell’s letter. He then goes on to answer most of the points raised and fulsomely acknowledges all the help and assistance he has received, from various companies and individuals but especially from Basil Miles and Charlie Cray to whom he attributes much of his success. The key paragraph, which sadly still holds true today in so many sports and was evident with tethered hydroplanes for far too long was that, "Had my progress been a little slower, and dignified speed of 40mph attained, I would most likely have been accepted as a reasonable sort of chap with perhaps big ideas, instead of what you will, a big head and lots of luck." He does add fuel to the fire by offering Mitchell one of his Dooling engines ‘to put in one of his ‘well designed boats’ to see if the results justify his most unworthy attack on my efforts.’ In a final dig George suggests ‘When with due modesty Mr Mitchell writes an article on winning an 'International' International, it will be interesting to note my comments’. George finishes by saying that perhaps it is time to bring this whole thing to an end? Probably akin to Albert poking the lion?

Certainly, Gerry Buck, who had already made his views on the use of foreign motors and components very well known, was of the opinion that it ‘was now impossible for an individual amateur to compete against the top notch firms’. He went on to draw parallels with what was happening in the Model Car Association ‘as a great a travesty of genuine sport as can be imagined’. This was all getting very personal and in some respects, quite offensive, but none more so that Mr Jepson of the Blackheath Club in the same issue where he stated at the beginning of his letter that "Mr Stone is quite welcome to his successes, hollow and meaningless though they may be". The final paragraph is even more damming as Jepson cites George’s remarks as ‘showing a lack of sportsmanship and understanding, fortunately rare amongst power boating folk, but is, perhaps, understandable as were Mr Stone more of a true amateur perhaps he would not be seeking his boating honours in the way he has’.

|

|

|

| Babs prop riding perfectly | The 'Lucky Swiss Boot' |

A fellow member of the Malden Club, Mr E.A. Walker said that ‘while not intending to take up the cudgels on behalf of Mr Stone (I think he is quite capable of doing this himself)’, he does consider that there is a need for a European wide class for ‘amateur built boats’, probably restricted to the 10cc class at present. In the same issue of 8th Dec, Frank Canning of Reading leapt to George’s defence saying that ‘Mr Mitchell lets himself down badly by his unsporting attack and lack of appreciation of the successes gained by Mr George Stone’. In the next telling paragraph he suggests that ‘there seems to be a class of model engineering snobs in the boat and car game to whom the use of a commercial engine is a crime; they attempt to cover their own frustration by decrying the efforts of others. The rest of the letter is equally supportive through the dismissal of Mr Mitchell’s other comments.

This level of attack was quite unprecedented and unwarranted by anything in the original article and it would hardly have been a surprise if George had dismissed the tethered hydroplane fraternity entirely and gone off in some other direction. There was little he could say in reply to some of these most unpleasant comments. It is perhaps of no surprise that the Kingsmere Club was formed late in 1949, taking a number of members from Malden, including George.

1950

The controversy continued into the New Year with that grand statesman of hydroplane racing Gems Suzor, pointing out that at the Geneva and Paris events, only 3 of the entries were home built engines and only one in the 10cc class. Although a committed home builder, Suzor was of the opinion that ‘everything should be done to facilitate the highest speed and that it was a real pity that so many clever model engineers are afraid of these commercial engines.

|

Mr Mitchell, a highly successful hydroplane man and builder of many complex and interesting motors, came back on the attack on 12th January with the view that buying a commercial motor was taking the ‘easy way out’ and that a further step down the road to ruin would be the importing of a completed commercial boat. He goes on to side with Gerry Buck having to compete against the Doolings with his home constructed cars and engines. Mitchell quotes an article that blames the high speed being obtained for death of tethered car racing in the States and notes the decline over here, finishing by saying that he does not want the same to happen to power boating. Right: George with Doug Reynolds at Fleet Pond |

|

In letters published on the 19th January, a Mr Gable was of the opinion that the amateurs could compete with the ‘top notch firms, it would just take a bit longer and in this he was proved to be correct by Dickie Phillips in 1955 and Terry Everitt 15 years later who both broke the outright record with home built 10cc motors. Mr Jackson reckoned that the correspondence had wasted too much space and had descended into a slanging match, which was of no credit to anyone.

On January 26th, John Benson in somewhat more conciliatory letter thought that the lake at Victoria was ‘much maligned’ and was of the opinion that boats could be designed to run at the Park and cited George Lines who had run his new boat there at 64mph without any signs of ‘diving or flipping’. He further goes on to say that the commercial engines have a distinct advantage over the home built ones in the 10cc class quoting Col Bowden’s book that mentioned the Dooling Brothers building 42 different prototypes of its famous 61 before going into production. The MPBA had recognised this inequality by introducing the C and C/R classes.

|

|

Arthur Weaver finally introduced a voice of reason on Feb 5th by saying that it should be a case of ‘live and let live’. Some enjoyed the element of competition, some to test their engineering abilities and some just because they like running boats. There is a bit of a sting in the tale though, seemingly aimed directly at George, as after he said that he saw ‘no occasion for mud slinging’ he says to the person who buys an engine ‘don’t attempt to appear superior, because you’re not’? Left; Babs with fishtail silencer for British running |

John Duffield of the King’s Lynn Club writing in March puts a much more practical slant on the situation and suggesting that all interested in the sport should express their views, whilst agreeing that a distinction should be made between ‘trade and private construction’. He does acknowledge the ‘excellent performance’ of ‘Babs’ but then congratulates Ken Williams on his achievements with the pre-war A Class ‘Faro’.

The correspondence continued for more than eight months with Ian Moore noting in June that the ‘antipathy between the various cults had gone on far too long and that to his knowledge more than a few enthusiasts had left the ranks, not because of the home made versus commercial argument, but because of the poor spirit of sportsmanship being demonstrated.’

Apart from the ‘Battle of the boilers’ this was by far the longest and most personal correspondence ever to sully the pages of ME and clearly illustrated the division in attitudes that existed and also goes a long way to explaining why the sport developed in the way it did from there on.

©copyrightOTW2016